Lev ha-Aryeh

(Venice : Giacomo Sarzino, 1612)

-

Originally printed in 1612, Leon of Modena’s Lev ha-Aryeh (“Heart of Aryeh”, a play on the Hebrew word for lion, and also his middle name), is the first Hebrew work of its kind on mnemonics and memory. It aims to help improve one’s memory, an especially important skill for those undertaking serious Torah study. It comprises 3 sections, each further divided into 12 chapters. Influenced by Aristotle and medieval Christians as well as Jewish scholars, Lev promotes and recommends some mnemonic techniques while critiquing several others commonly used in that era, including magic and drugs – particularly the consumption of baladhur, the sap of the marking-nut tree.

Viewed from several contextual angles, Lev proves even more interesting. In the Hebrew Bible, the verb infinitive “to memorize” appears 169 times. More than a mere word count, this number points to the premium placed on the ability to remember, and memorization, as an essential basis of the oral Biblical tradition meant to assure the Jewish religion and people’s survival. Other medieval faiths also considered memory training an integral component of their educational systems. Religious leaders – whether Jewish or not – also looked at the growing availability of books and the consequent possibility of ideas differing from theirs. They recognized that a constantly-reinforced memory could serve as a bulwark for their constituents’ moral fortitude against such ideas. The conception, writing and reading of a book – like Lev – for such a purpose therefore might seem somewhat ironic.

In Modena’s era, popular memorization methods included the use of abbreviations, lyrical recitation (particularly for the Mishnah) and repetition, along with those previously mentioned. His more classical mnemonic stratagem, relying primarily on places and images, finds its counterpart in the 14th century revival, led by Thomas Aquinas, of the classical art of memory techniques in the tradition of Simonides of Cheos. Those techniques classified memories into 2 types: natural; and artificial, or those established from places and images. Aquinas expanded upon that duality to create his 4 basic rules that would dominate memorization techniques during the Renaissance.

Modena himself relies considerably on Aristotle’s De memoria et reminiscientia to herald memory as one of the sensitive soul’s 4 powers, referring to the classical techniques as did Aquinas. He believed them to be natural and so the safest, most beneficial, and useful for improving recall. One such method he suggests: designing a folio, to best remember what has been inscribed on it; he draws a parallel between this and the Hebrew Bible scribes’ practices for creating scrolls. Lev concludes with a mnemonic, created by Nathan Ottolenghi, for Maimonides’ table of that Bible’s 613 positive and negative commandments.

Given Modena’s lifelong staunch defense of rabbinic authority, it seems unsurprising he would dedicate an entire treatise to memory. When he penned Lev, the modern printing era had only existed for little more than 150 years, but his concerns over memory echo those of earlier rabbis anxious that it could render memorization, recall, and Jewish oral tradition practically and profoundly unnecessary. Their fears permeate early Hebrew printing; Lev represents an attempt to mitigate their trepidation by demonstrating the new medium’s potential to serve and strengthen existing traditions.

-

Venice-born Leon of Modena (Italy) aka Yehudah Aryeh Mi-modena (1571-1648), descended from a French family who had settled in Modena. Little information exists on Leon’s early life, primarily spent in Ferrera, but it does indicate his academic precocity extended well beyond traditional Jewish studies to music, philosophy, mathematics, and poetry as well as fluency in both Latin and Italian. Small wonder, then, that he wrote his first work, the Hebrew-Italian poem Kinah Shemor, at age 13.

His fiancée Esther died in 1590; he then married her sister Rachel. Leon returned to Venice to obtain his rabbinic ordination, but only earned it after the local bet din (rabbinical council) delayed it by raising the minimum age required – twice. Ironically, he never found a permanent rabbinic posting; and he also refused to accept a Parisian university’s offer of an Oriental languages chair as it required he convert.

Instead, his peripatetic job history includes work as a proof-reader, amulet maker, bookseller, interpreter, teacher, merchant, writer, and matchmaker. Notably, Leon’s two longest-lasting careers seem to reflect his higher and baser instincts: he served as a Venetian synagogue’s cantor for over 40 years, yet was also a lifelong, professional gambler. His writings sometimes incorporate the latter: in Chayei Yehudah – the first full-length autobiography written in Hebrew – Leon addressed his gambling addiction, and he also wrote a halakhic (Jewish law) treatise against the evils of card-playing. As well, his Lev ha-Aryeh (1612) – a copy of which the JPL holds – deals with possibly-related memory training skills.

However, Leon’s polemics against Kabalah became his best-known, perhaps most notorious works. His stance, deeply unpopular at a time when most Italian rabbis supported or practiced Kabalah, resulted in many of his texts only being published long after his death. For example, in Ari Nohem, he posited the Zohar’s modern provenance. Later academic inquiry proved him correct – but it took until 1840 for Ari to be printed.

Besides being an anti-Kabalist, Leon found renown as an intermediary for Christians on Jewish practice and tradition. His Historia de gli riti Hebraici (1637), one of the first texts written about Judaism for a non-Jewish audience after those by Josephus and Philo, was heavily read and translated.

Leon’s works also include – among others – Sod Yesharim (1594), Galut Yehudah (1612), Sha’agat Aryeh (1622), Ben David (1636) and Phi ha-Aryeh (1640), as well as many volumes of responsa and poetry.

In Chayei, Leon reveals his and Rachel’s unhappy marriage as just one of several intimate details of his somewhat tragic personal life. He also had 3 adult sons who all predeceased him in circumstances including alchemical poisoning, murder and estrangement; and a rift between Leon and his favored, widowed daughter’s new husband led to the younger couple fleeing, leaving behind their son in Leon and Rachel’s care. The quarrel no doubt furthered strained Rachel and Leon’s relationship, and perhaps contributed to their deaths within a two-week span in March 1648. The Jewish community, and many Christian writers in Italy and across Europe, eulogized him.

Leon’s legacy remains complex. 19th century scholars studied his manuscripts through the lens of contemporary Judaism rather than taking a contextual approach. Their opinions widely varied: some saw him as opposed to traditional Judaism and a forefather of Reform Judaism; others against Reformism labeled him as merely a gambler and heretic. A more nuanced interpretation might view Modena as one of the last of the medieval-era rabbis, who argued for continued rabbinic authority in the face of attempts to limit their power.

-

Koscielec (Poland)-born Giacomo Sarzino (né Ya’akov ben Yosef Soresina c. late 15th-century – 1641) originally studied the shehitah (Kosher butchering) trade from Krakow rabbi Tzvi Buchtner, author of a comprehensive series of related glosses and notes to Rabbi Jacob Weil’s Shehitot u-Bedikot. Giacomo then immigrated to Venice, at a time when Polish rabbis and related religious functionaries saw the Jewish Ashkenazi community there and in other Italian regions as lapsed in their religious knowledge and practices.

In Venice, Sarzino wrote Sefer ha-Nikur (1595), a trilingual (Hebrew-Italian-Judeo-Spanish) summary of Buchtner’s work that was published by the Di Gara press. Nikur includes a prefatory poem composed by a proof-reader then working for Di Gara: Leon of Modena. Their working relationship would soon expand.

Giacomo subsequently worked as an editor and typographer for the Venetian Di Gara, Zanetti and Bragadin presses. As the Bragadin family members increasingly detached themselves from their press’s day-to-day business – interested only in its profits – Sarzino, among others, most likely actually operated the press and used its facilities for his imprint. Among the books he published were two written by his former Di Gara co-worker, Leon of Modena: Lev ha-Aryeh – a copy of which the JPL holds – and Galut Yehudah (both 1612).

Over Sarzino’s printing career, he produced Hebrew and non-Hebrew works. In fact, he was one of the major printers for the Incogniti, a group of Italian literati responsible, by some estimates, for an astounding 50% of the approved texts printed in Italy between 1632 and 1642. He died in Venice.

-

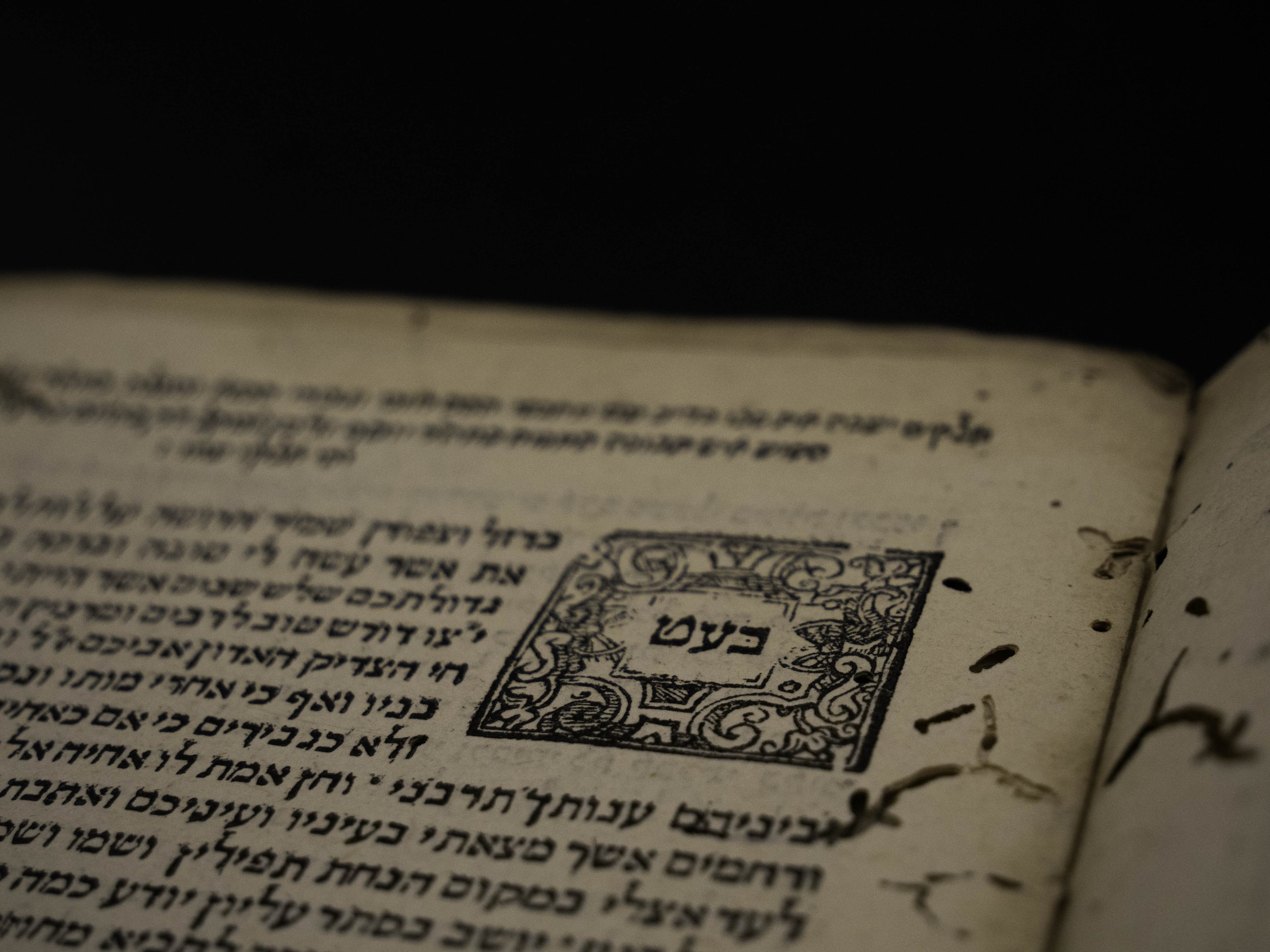

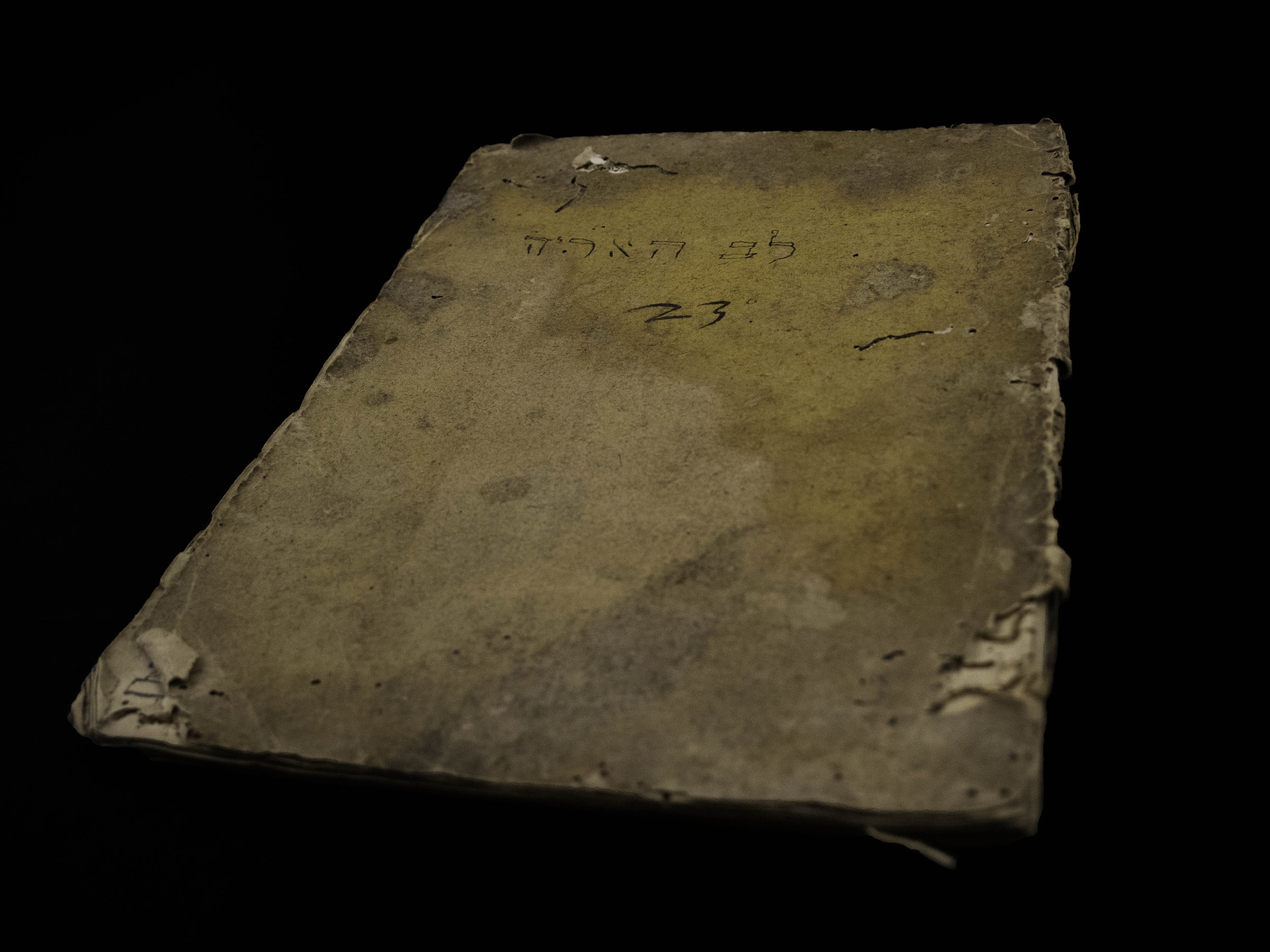

The Library’s copy of Lev’s 1st edition (1612), a very slender quarto volume, measures 20 x 14 x 0.5 cm. Its simple paper sleeve cover, which is not the original, barely remains attached to the pages which like the cover are extremely damaged and bug-eaten. The cover also bears a short, penned Hebrew title inscription in shaky block letters. However, upon opening the cover, an ornate title page decorated with archetypal gates announces the title, author, and other pertinent information in a combination of block print and Rashi script typeface. At bottom, the Latin “Con licenza de’Superiori” indicates the printer obtained the right to publish this work.

The text proper is printed in block type; Rashi script is used throughout for subtitles and for the list of the 248 positive commandments that spans the 3 final leaves’ rectos and versos. Throughout, the printing regularly appears smudged – typical of early publishing. The foliation starts on the 2nd leaf, with an error: rather than the expected Hebrew letter bet (indicating “2”), we find a poorly printed dalet (“4”). The error reoccurs on the 4th leaf, where a bet appears instead of the dalet. Notably, on the 15th leaf, a printed yud-hey (“10-5”) appears; as this combination happens to be the Tetragrammaton’s initial 2 Hebrew letters, the letters tet (“9”) and vav (“6”) normally serve as a substitute. Ottolenghi’s recapitulation of Maimonides’ list of the 613 Biblical commandments in unpaged foliation ends the work. However, its last 3 pages – including the censor’s full, dated statement of approval for Lev as a whole – are absent.

There is no marginalia within the work. However, the front cover has the number “23” scrawled in ink beneath the title. The inside cover page bears the pencilled inscription “Venice 1612 / Very rare / 50.00”. Presumably, a bookseller marked this, with the number most certainly indicating the book’s price – although with no currency symbol present, one cannot ascertain the exact figure, let alone determine the vendor’s location. Still, from this information, one could guess JPL co-founder Yehuda Kaufman possibly purchased this copy in New York, as he regularly travelled there to buy antiquarian books.