Ma'aseh Toviyah

(Venice : Stamparia Bragadina, 1707)

-

Kats was a physician and it is logical that so much of his “Works of Tobias” should focus on subjects of a medical nature; some of the theories that he advanced were groundbreaking, especially in the area of pediatrics.

It is not only in the medical sections, however, that Kats shows an eagerness for new knowledge while still adhering to traditional thoughts. For example, in part two of Maʻaśeh he includes illustrations of astronomical and mathematical instruments – including an astrolabe – but also discusses, and roundly dismisses, Copernicus’ system on religious grounds.

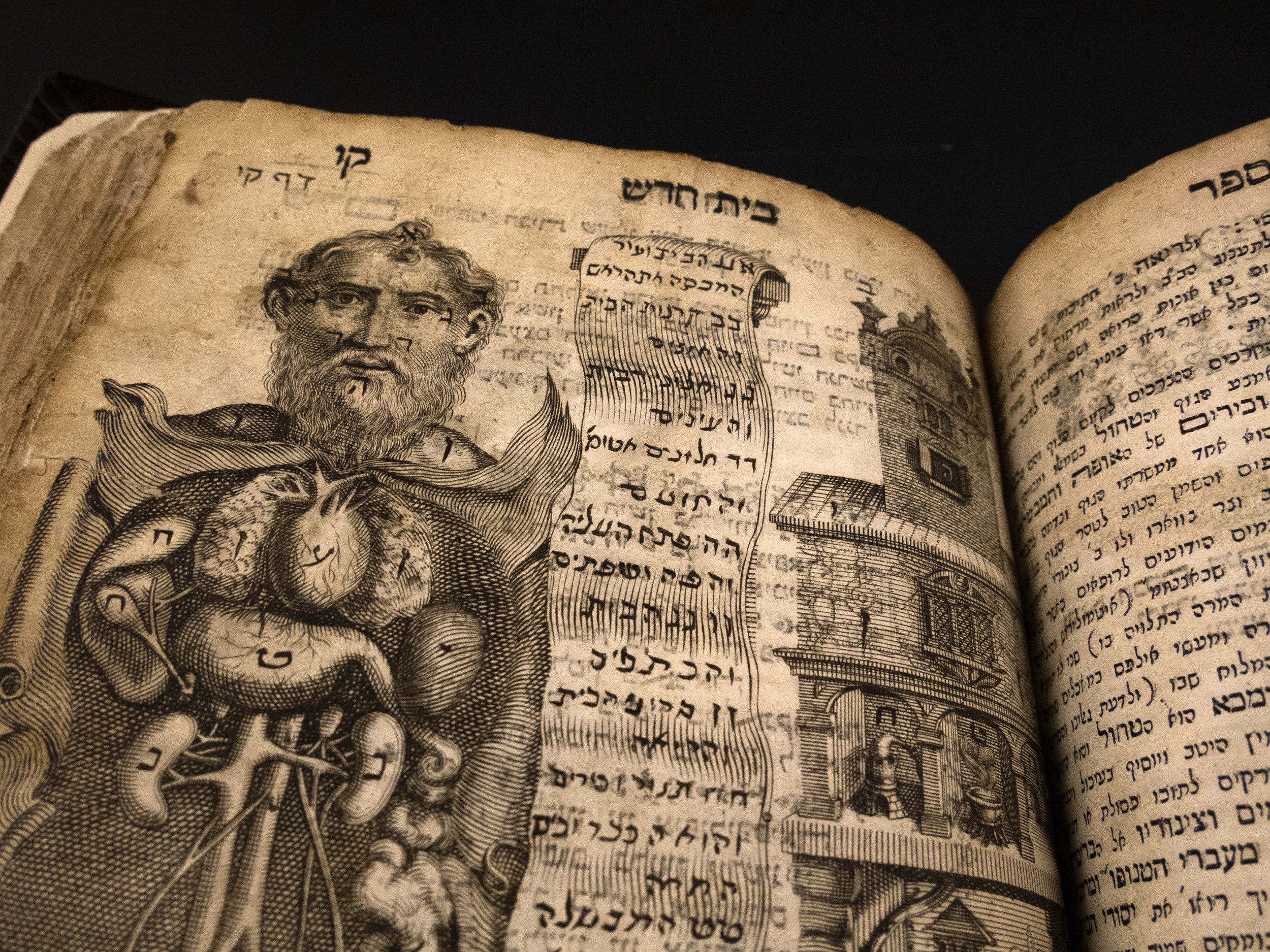

However, Maʻaśeh’s most interesting facet above all is an illustration that has made it a famous work. In the medical section, Kats includes an allegorical depiction of the body as a house, effectively comparing the body’s inner workings to the rooms in a house.

His remedies are generally those notorious for his time: laxatives, emetics, cupping glasses, and bleeding. However, he strongly dissents against the still-popular Galenic system when discussing stomach diseases, for example. He provided the first description of the plica polinica, devoting quite a bit of time to this disease common in Poland at the time. He also demonstrates support for the Harvey blood circulation systemic, further showing his straddling of the old medical world and the new developments making ground amongst physicians across Europe.

-

Metz-born Toviyah Kats (1652-1729) was also known as Tobias Kohn, Tobiasz Kohn, Toviyyah ben Moshe ha-Kohen, and Tuvia Ha-rofeh. His lineage shows a pattern of medical and nomadic influences: Eleazar, his physician grandfather, moved from Palestine to Kamenetz-Podolsk (Poland), while Toviyah’s father Moses moved to Metz in the face of the Chmielnicki Uprising and the resultant persecution of Polish Jews. When Toviyah was 9, his father died, and Toviyah and his older brother were sent back to Poland to be raised by extended family.

After receiving a traditional Jewish education in Krakow, Kats studied at universities in Frankfort-on-the-Oder and Padua, where he obtained his doctorate in medicine. He then returned to Poland to practice medicine for some time, then went to Turkey about 1686. There, he served as court physician to 5 successive Ottoman sultans.

Reflecting his considerable travels, Kats knew of at least 10 languages, with varying degrees of fluency. Clearly, his talent as a polyglot benefited his practice, allowing him access to European and Middle Eastern medical knowledge which also heavily informed Ma’aseh. He also repeatedly and publicly criticized his Frankfort professors’ anti-Semitism – while equally lamenting Kabalist Jews’ commitment to miracles rather than science.

In 1724, Kats went to Jerusalem, where he lived out his remaining years.

-

In our collection, from the earliest books onward, a printer’s given name and surname’s appearance on a title page is almost a given. One rarely finds a printing company credited there instead –yet one such contemporary firm began making its mark with books like Maʻaśeh. Stamparia Bragadina (literally “Bragadin’s Printshop”) was founded some time before 1550 by Alvise Bragadin.

Born sometime in early 16th-century Venice, Alvise came from one of its wealthiest, most influential Christian families. Although we do not know for certain when he first began printing, in Hebrew or otherwise, the most commonly accepted academic research suggests the Stamparia’s first Jewish production was the Mishnah Torah (1550).

However, Bragadin’s business timing and practices rapidly proved unfortunate. Notably, he and fellow printer Marco Antonio Giustianini together first forced rival printer Daniel Bomberg to cease operations; Alvise’s subsequent legal dispute with his erstwhile ally over competing Talmud editions eventually resulted in the Church’s Talmud burnings in 1553, and Venice’s 1554 ban on Hebrew book printing for 9 years.

Nevertheless, with the ban lifted, the Stamparia resumed printing and continued with remarkable success even after Alvise died in 1575. His son Giovanni took over the business, which then operated under a near monopoly on Hebrew book printing for almost 60 years. Their books exchanged hands all throughout Europe, North Africa, and a considerable portion of the Middle East. The Bragadin family maintained the press’s fortunes until its decline in the mid-18th century.

-

Our copy is from the first edition, printed in 1707 in Venice by the Stamparia Bragadina. Maʻaśeh was subsequently reprinted in 1715, 1728, 1769, and 1850. It measures 23.5 x 17 x 3 cm, smaller than a modern encyclopedia and certainly much smaller than what we would expect of a scientific one. Its title page is missing, as are an uncertain number of leaves towards the book’s end — which indicates a larger problem with our copy’s condition. Most of the book’s initial leaves, and its last 18 leaves, show signs of significant damage and have been extensively repaired. Given the extensive foxing and wormholes throughout and the consistent, comprehensive marginalia, it makes sense that someone thought to preserve the work’s content and these additional notes by rebinding it – with beautiful results.

The new rebinding, rewrapped in sturdy butter-soft brown leather, is in almost-perfect condition. Although it is obvious that no attempt was made to ensure it would match the original, it makes this book much easier to handle than many of its counterparts – an especially impressive feat, given the precarious state of some of its pages. On the spine, gilt letters at the bottom indicate the 1707 printing date; while at the top, a red leather patch with similar gilded Hebrew letters spell out the work’s short title. The new, good-quality end-pages show visible chain-lines.

The title page is missing. However, it appears Maʻaśeh was conceived as a 3-volume work: Volume 2’s title page is placed roughly 2/3rds from the book’s start, and gives us an idea of Volume 1’s title page layout. Volume 3’s cover, identical to that for Volume 2, appears shortly thereafter. It consists of heavy, ornate gates crested by a shell with a vase on each side. An ivy-wrapped column flanks each side, with greenery carved into the bottom. In the remaining miniscule central space, Hebrew text indicates the volume’s contents and place of publication, along with the printer’s name in Latin characters.

Within the volume, a decorative heading marks each section. Its ornamentation mimics the simpler title pages for which the printer was known. Botanical stamps fill nearly 2.5 cm of page space above each chapter’s title underneath. Each section is divided into chapters, although there are no page changes — and often no line breaks — denoting this. Rather, they appear at the beginning of the line where the section starts and within the text, as one might expect to see an illuminated letter.

From Maʻaśeh’s initial appearance until today, its copious illustrations have proven its most interesting facet for readers serious and casual alike. Of those images, predominantly in the work’s astronomy and hygiene sections, the most famous appears in Volume 2’s second part known as “The Book of a New Home”. It depicts and describes the human body and its components by using the analogy of a house.