Masekhet Tamid min Talmud Bavli

(Grodno [Poland] : stanislav Augustos Melekh Polin, 1789)

-

Tamid (literally, “Constant” or “Ongoing”) is the shortest tractate of Kodashim (“Holy Things”), a major Talmudic division dealing largely with the ancient Holy Temple’s religious services, maintenance and design, as well as ritual slaughter of animals. It outlines the Temple services for the daily morning and evening sacrifices. Many scholars believe it to be one of the earliest Mishnah sections, composed shortly after the Holy Temple’s destruction in Jerusalem.

-

Asher ben Jehiel (c. 1250-1327) was likely born in Cologne, then still part of the Holy Roman Empire. Frequently referred to as Rabbeinu (Our Rabbi) or the Rosh (Head), he came from a family well known for their piety and devotion to learning. Other than his religious activities, Asher became an independently wealthy moneylender, perhaps following in his father’s line of work.

In 1286, during a period of persecution against the Jews, the Empire captured and imprisoned one of Asher’s teachers, the distinguished Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg. Asher’s father attempted to pay a ransom for Meir’s release, but the rabbi refused this in order to discourage the jailing of other rabbis for similar expected payments. This led to Asher taking on Meir’s position as rabbi in Worms, but in 1305 he too was forced to flee. Asher died in Toledo (Spain).

Asher rarely exercised leniency in his halakhic decisions, even when the circumstances justified it. However, he achieved acclaim for his legal reasoning, his ability to provide comprehensible summaries of long, complex Talmudic discussions, and for bringing what he considered the more authoritative Ashkenazic traditions, teachings and methods of the Tosafists to Spain. His aversion to secular teachings, and his particular criticism of philosophy, led him to become the leader of the Spanish faction against Maimonides.

His work includes the Piskei ha-Rosh, a comprehensive elaboration on Talmudic laws that clearly and concisely indicates and explains them from their original sources to major opinions and final decisions on them. His other works include Orchot Haim, an essay on ethics for his sons; Tosefot ha-Rosh, glosses on the Talmud; commentaries on the Mishnah tractates Zeraim and Tohorot, and a volume of responsa. His influence extended to two subsequent authoritative codifications of Jewish law: his renowned son Jacob’s Arba’ah Turim and Joseph Karo’s subsequent Shulkhan Aruch, in which Karo places Asher on a par with Maimonides and Isaac Alfasi as determinants for his ultimate rulings. Almost every edition of the Talmud since its first printing includes Asher’s work.

-

Nearly 200 years before the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth emerged in 1569 and united the territories of the Polish Crown Kingdom and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Jews began settling in Grodno (Poland). Despite subsequent military and political upheavals, the community continued to grow along with other Jewish ones in the country – and by the late 1700s, approximately 750,000 Jews lived throughout the Commonwealth, or about 6% of its population.

The printing trade also had roots predating the Commonwealth’s establishment: in the Polish kingdom, a Krakow press began as early as 1465 while in the Duchy, a Vilna printer produced an excerpt of the New Testament in 1524. Despite these achievements, however, at least two factors hindered the Commonwealth’s printing industry over most of its existence.

First, a given region or city generally fell under the control of either the monarch, or the local nobles who collectively elected him in the country’s Sejm or parliament. Since the granting of printing charters also depended on either royal or ‘private’ – i.e. local noble – assent, no truly nationwide printing development strategy emerged. For example, the regime established formal printing centres in only 7 regions – usually situated in provincial capitals like Krakow, Warsaw and Gdansk. As well, many of the Commonwealth’s churches, libraries and scholarly institutions apparently preferred the foreign publishers’ quality and variety of books, to the extent that by the mid-1760s, book imports well exceeded the local presses’ sales.

However, up until then, the Jewish community’s synagogues and schools had proved a steady if small market for Hebrew printers. The country’s Jewish printing history extended back to 1534, when the Prague-trained Helicz family of typesetters, printers and compositors set up their Hebrew press in Krakow. It became the region’s first firm of its kind; while a similar concern in Olesnica (Silesia) predated it, Olesnica fell outside of the Commonwealth’s borders at the time. Other Hebrew printers established themselves around Lublin in the following decade. Still, the increasing demand for Hebrew books outstripped these Jewish publishers’ capacity. By 1764, a new king interested in promoting culture and business would influence that situation in a small but ultimately powerful way – as shown by Tamid’s title page, which lists its printer’s name in Hebrew as “The Press of Stanislaw Augustus, King of Poland”. The monarch’s patronage would enable the book’s actual printer, then based in Grodno, to emerge as a prominent Jewish publisher for at least a century across Eastern Europe.

Stanislaw August Poniatowski, aka King Stanislaw II, ruled the Commonwealth from 1764 until its dissolution in 1795. He had controversially won the election to that post thanks to the support of Russian Empress Catherine the Great, with whom he had a romantic dalliance. Notably, Stanislaw became the country’s preeminent arts patron during its belated Enlightenment period. Among many other cultural involvements, including hosting weekly cultural salons and founding Warsaw’s national theatre, he founded one of Poland’s first newspapers and supported numerous writers, poets, bookstore and library owners, and publishers – including those in Grodno.

In 1788, King Stanislaw II organized Grodno’s first printing press under the direction of his Lithuanian-born treasurer Antoni Tyzenhaus. Between 1788 and 1792, Boruch Romm, a Hebrew printer, leased this press. He likely produced our edition of Tamid, given its year of publication. Romm and his press relocated to Vilna in 1799, where it grew rapidly. It printed primarily halakhic (Jewish law) works, and earned particular fame for an 1886 edition of Talmud that played a pivotal role in a dispute between Romm’s press and a rival firm in Slavuta (Ukraine). That controversy resulted in the authorities forcibly closing the rival press and imprisoning its owners, while awarding Romm a formal publishing monopoly.

The king’s scholarly and cultural pursuits eventually garnered him the honour of being the first person other than British royalty to earn membership in England’s Fellowship of the Royal Society, as well as similar awards from science academies in Saint Petersburg and Berlin. However, despite these achievements, his attempts to strengthen the Commonwealth failed. It was partitioned 3 times during his rule – the last in 1795, after which he abdicated and lived out his final years in Saint Petersburg, a prisoner in all but name.

-

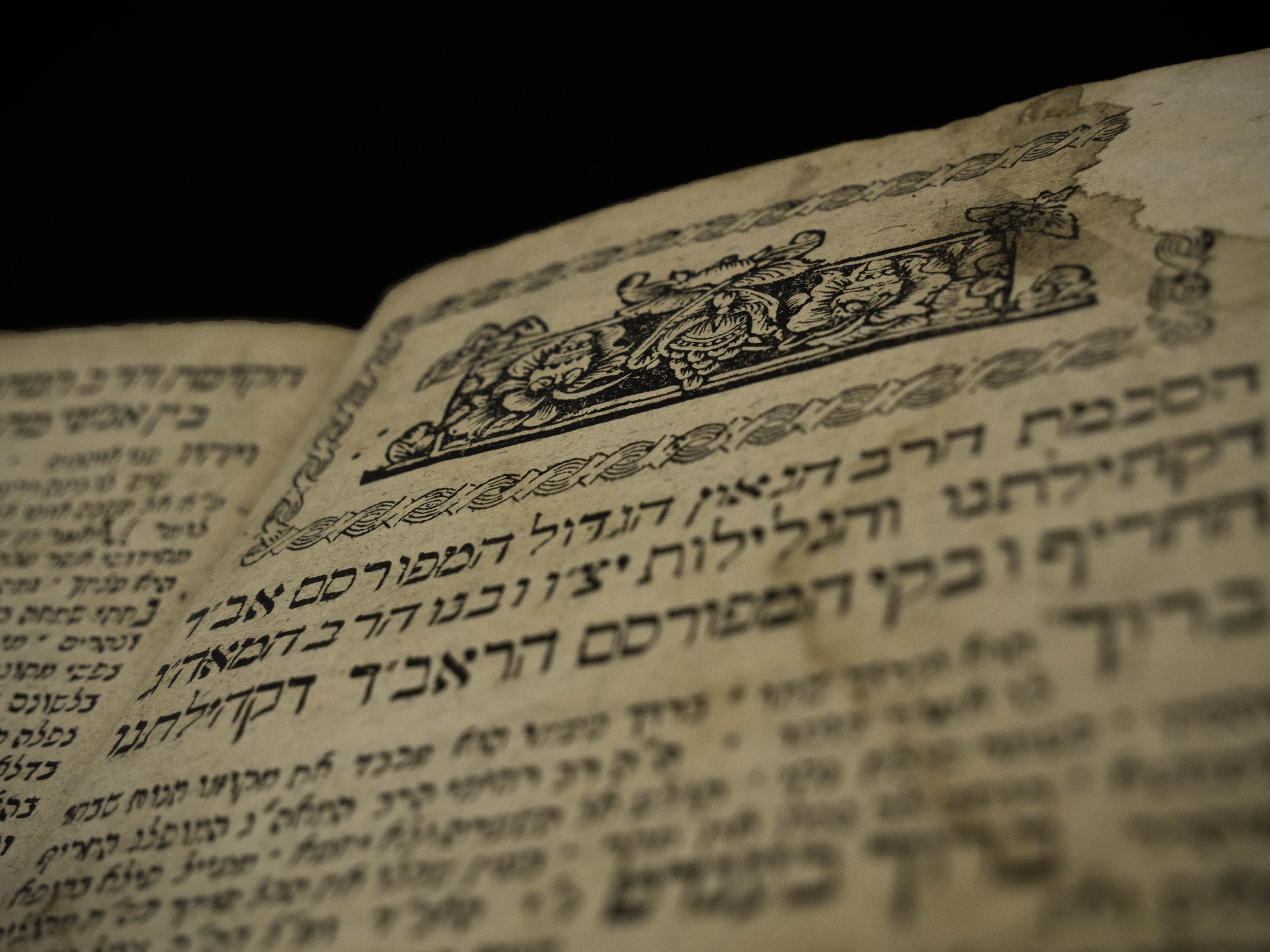

Our copy measures 19 x 11.5 x 1.5 cm, about the size of a small modern paperback. Its half-leather binding, with a cracked brown-leather spine, has peeled away in some places to reveal the stitching beneath the spine and the corners, although it is wearing away on the edges. The faded, green-and-brown marbled cover is almost certainly not the original; neither are the end pages, which postdate the text pages. On the front page, a mould spot 5 cm in diameter has rendered blurred writing, in brown script along the outside vertical edge, completely illegible in some places. The mould spot also affects the page opposite, and the title page beneath that.

The title page’s left upper corner and entire bottom quarter are missing, even with some subsequent repair work with pages matching the new end pages. Only the extreme topmost portion of what appears to be a printer’s mark or decoration remains. A fading, black-ink stamp, along with Cyrillic text, overprints the title itself. The first 3 pages’ corners have been repaired, with handwritten text replacing the missing original; the rest of the pages are in fairly good, entirely intact condition except for the last 3 which have also been repaired, although the last page’s repair work is also deteriorating. Other than sustaining a considerable amount of foxing, the pages otherwise bear only minimal bookworm damage. Some pages are detaching from the binding, especially near the bottom. Mould – on the back end page – and the back cover’s bloating indicate water damage to the book at some point.