Sefer ha-Shorashim

(Salonika : moses soncino, 1533)

-

Kimhi wrote Sefer ha-Shorashim (“The Book of Roots”), a Biblical Hebrew lexicon, first printed around 1480 under the name Ḥelek ha-Inyan (“Section On Matters”). He originally intended it, along with his Ḥelek ha-Dikduk (“Section On Grammar”), to form Sefer Mikhlol (“The Book of Completeness”), a Biblical philological treatise. However, Mikhlol became the standard title used for Dikduk only, which remained the leading work of its kind for many centuries, reprinted as late as 1965. In Shorashim Kimhi, introduced many new etymologies: heavily influenced by his father Joseph’s research as well as Jonah ibn Janah’s dictionary Kitab al-Usul, he showed parallels between Hebrew, Aramaic, and Provençal.

Kimḥi was criticized as a highly unconventional grammarian by figures like Joseph ibn Kaspi, Profiat Duran, David ben Solomon Ibn Yaḥya , and Abraham de Balmes. He found advocates, however, in Abraham ben Elisha ben Mattathias’s Magen David, Solomon ibn Melekh’s Mikhlol Yofi, and Elijah Levita’s writings. Ultimately, with the success of Kimhi’s Mikhlol and Shorashim, most of his predecessors’ works sank into oblivion.

-

Narbonne-born Rabbi David Kimhi (ca. 1160-1235) was the son of Joseph Kimhi, a renowned grammarian who had fled there following the Almohad persecutions in Spain. Joseph died early in David’s life; he was raised by his elder brother, Moses. In his early adulthood, he taught Talmud for a living.

Known by his Hebrew acronym Radak, Kimhi followed his father’s path as a grammarian, also becoming a philosopher and — as he is best known for today — a Biblical commentator. In that role, he employed his linguistic knowledge, focusing his analysis on the text’s language and grammar to determine its meaning and understanding. His commentaries also included effective rebuttals of Christian attacks on Judaism, frequently calling attention to their misinterpretation of Bible passages.

Besides Shorashim and Mikhlol, Kimhi’s works as a grammarian included Et Sofer (1864), an abridgement of Mikhlol written as a manual for those creating Bible scrolls. Kimhi regarded Et as a necessary response to what he considered widespread ignorance among scribes. His interest in establishing the ‘correct’ Masoretic Biblical text – attested by his travels in pursuit of old Biblical manuscripts, and various observations in his commentaries – also reflected his concern with the contemporary proliferation of Biblical manuscript traditions.

Jewish academia accorded Kimhi high honour, referring to his writings by a Talmudic phrase that coincidentally plays on his surname: “If there is no flour [in Hebrew “kemah”, from which “Kimhi” derives], there is no Torah”. As well, one can note his profound influence on Renaissance Christian Hebraists: Reuchlin’s Rudimenta Linguae Hebraicae and Lexicon Hebraicum (1506), Santes Pagninus’ Institutiones (1520) and Thesaurus (1529) basically rework Kimḥi, while Sebastian Muenster’s writings betray his influence heavily.

-

Moses Soncino, the likely printer of Shorashim, was a member of one of the earliest and still best-known of Jewish printing dynasties. In 1454 his great-grandfather Simon, and Simon’s brother Samuel — both descendants of Talmudist Moses of Speyer — travelled from Fürth to settle in the Italian town of Soncino, taking that as their surname. They apparently established a banking business, but when the town opened a public loan office and forced the Soncinos to close, Simon’s grandson physician Israel Nathan and his sons Joshua and Moses turned to printing, in 1483.

Their press’s first book was Berakhot (1484), the first Talmudic tractate ever printed, with an arrangement of commentaries that is now standard and a format for religious texts which Jewish and non-Jewish printers alike followed. Under Joshua’s stewardship, the press also printed the first complete, vocalized Hebrew Bible (1488). This, along with innovations to ensure typographical clarity and textual accuracy earned the Soncino press acclaim. As an aside, Joshua added the well-known Soncino printer’s mark – a tower.

By 1490, however, the Milanese duke’s religious persecutions resulted in the family’s expulsion from Soncino. This, along with Joshua’s death in 1493, might have spelled the press’s end. Instead, Moses’ son Gershom, having taken over the press from Joshua, decisively spurred the business’s growth. Brilliant, prolific and ambitious, he published over 150 religious and secular texts in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and Italian. A devout Jew, Gershom also courted controversy by reinstating excised portions of Jewish works he knew the Church would find objectionable, and mounted a legal challenge charging Aldus Mantius stole – rather than invented – the iconic italic typeface. Still, his publications garnered much respect from luminaries like Martin Luther, who used Gershom’s Hebrew Bible (1594) for his German translation.

Meanwhile, Gershom’s extended clan settled and printed throughout Italy and the Ottoman Empire. Moses, for instance, moved to Salonika sometime around 1520-21, as the town was already a well-known haven for Italian and Iberian Jewish exiles.

In Salonika, Moses’ first release was Joseph Albo’s Sefer ha-ʻIḳarim (1521). He also printed the 2nd edition of the text of the Mahzor Catalonia, a lavishly illustrated 13th century manuscript of the Barcelona Jewish prayer rite smuggled out of Spain in the Inquisition’s wake. Moses also apparently produced books in Rimini. However, after Shorashim, he went to Constantinople where his great-grandson Eleazar succeeded him.

By the late 16th century onward, no Soncino remained directly involved in printing but the family name retained its cachet. In 1924 a group of German scholars — including Albert Einstein — founded a Soncino press in Berlin, closed by the Nazis in 1937. In 1929, a British-based bilingual English-Hebrew press adopted the family moniker and still exists today.

-

Moses Soncino printed our copy of Shorashim in 1533 in Salonika (now Thessaloniki) in Greece, where his press operated around 1521 to 1533. It was his last known publication there.

It measures 27 x 19.5 x 3 cm. A beige cloth binding, fraying along the edges, corners and spine -- from which it has begun to separate -- replaced the original one. The work’s title and author’s name are inscribed in pen along the spine; interestingly, the former appears in block print, while the latter is in script.

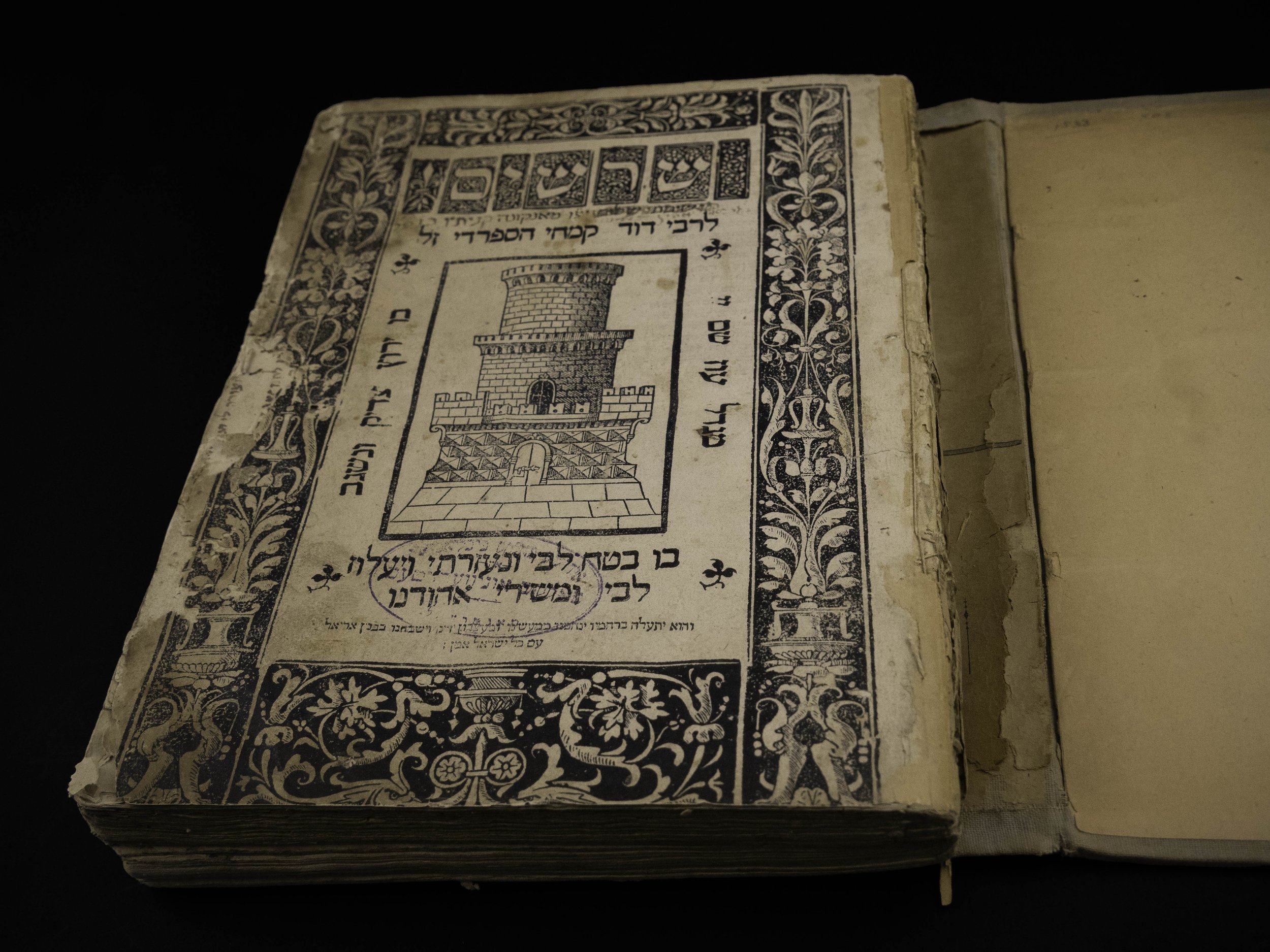

The title page contains ornate decorations, framed with a floral motif and pottery against a dark background wrapping around all four edges. Each title letter is encased in its own, small floral frame. Notably, the entire title ends with a fleur-de-lis motif. While the lily was a popular symbol in early Jewish art -- particularly in 1st and 2nd Temple architecture -- and perhaps also references Kimhi’s Provençal roots, it was more strongly associated with France’s Monarchy, Christianity, the Holy Trinity and the Virgin Mary by the time of this book’s printing. The choice of this emblem seems even more puzzling when one considers that Italian Jews published this edition – and that, within the Ottoman Empire.

Underneath this puzzle, the Soncino printer’s mark of a three-tiered, crenellated tower appears.

Most of the pages, in precarious shape, suffer from bookworm damage as does the spine, though the stitching remains intact. A close examination of the repair work done on the spine reveals that an English-language newspaper was most likely used for the rebinding, although little of it remains. The pages have been heavily repaired, mostly along the edges where the worst bookworm damage occurred. The paper used for the repairs, either blank or written upon generally in Hebrew or Italian, mostly seems to predate the paper industry’s innovative shift from cloth to wood pulp paper in 1843. Unfortunately, the methods used for many of these repairs resulted in the hiding of the gloss on one side of each page.

The book ends with the words “Shlome Soncino”, in Hebrew. An apparent attribution of responsibility to Joshua Solomon Soncino, it belies the fact that he had died 4 decades earlier. Above this, two Hebrew letters (both Shin), enclosed by the trefoil leaf occasionally present in the book’s margins, serve as a brief colophon. This is of particular interest, as the JPL owns 2 other roughly contemporaneous Soncino-produced works (Moses Soncino, Rimini 1524; Moses Parnas for Eleazar Soncino, Constantinople 1547). These two contain similar title page frames to this book, but the trefoil and ending Hebrew letters only appear in this work.