The Jew

(London : C. Dilly, 1797)

-

First printed in 1794, British dramatist Richard Cumberland’s play The Jew was staged that same year. Its audience encountered a character never seen before onstage: a positive representation of a Jew, who just happens also to be the play’s hero.

It is worth noting Cumberland’s general popularity allowed him the opportunity to stage the play in the first place. A veteran playwright, he leveraged his clout to undermine prejudices. In that aspect, the play is not unique, being one of his several “rehabilitation” dramas. Sheva, its protagonist, is frequently regarded as the ancestor of “good Jews” in literature created to provide a foil for the anti-Semitic rhetoric popular on English stages and propaganda material between 1753 and 1794.

The Jew is often read as a revision of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, the vehicle for drama’s most famous and notorious Jewish character : Shylock — Sheva’s polar opposite. Though the play’s plot mirrors much of Merchant’s, it also updates it to reflect 18th-century stage traditions, including a complete overhaul of the romantic plot, and – most importantly – it highlights Sheva’s charitable nature.

Surprisingly, while its mostly non-Jewish audience warmly received The Jew, England’s own Jews did not think much of it. By comparison, after numerous engagements in Ireland under the title The Benevolent Hebrew, American Jewish and non-Jewish audiences acclaimed the renamed play, with multiple performances in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, Providence, Norfolk, and Charleston. As to these differences in Jewish reaction to it, literary professor Eve Tavor Bannet offers several explanations.

The first is that the play costumes Sheva as a poor Ashkenazi Jewish peddler, with a stereotypical Ashkenazi accent. However, his backstory clearly indicates his status as a refugee from the Spanish Inquisition. England’s contemporaneous Sephardi Jews could not help but react with revulsion to this association of their now-wealthy, highly-assimilated community with a downtrodden, visibly-recognizable Jew, which they saw as a step backwards in spotlighting their perceived otherness.

Furthermore, many English Jews – whether Sephardi or Ashkenazi – felt The Jew highlighted several issues reminding, and therefore possibly provoking, audiences about English Jews’ precarious legal status. Cumberland referenced the fact that the 1290 expulsion decree had never been repealed, making Jews non-persons whose English residency depended solely on the monarch’s whims. He also had Sheva interact with non-Jewish English merchants, who in reality were some of the most aggressive opponents against of Jewish inclusion into English society. As well, after France’s post-Revolutionary emancipation of Jews, and the concurrent political unrest across Europe leading to increased Jewish emigration to England, The Jew upheld England as a normative Christian society – where Jews remained an alien group always subject to accusation of divided loyalties.

By contrast, the far smaller American Jewish population faced a far different legal and social environment. From the 1740s on, Jewish immigrants to the then-colonies required only 7 years to become eligible for naturalization. During the War of Independence, the wealthiest Jewish families demonstrated their loyalty to the Revolution, contributing both financing and manpower; afterwards, Jews became full citizens with the same civil rights, including voting, as all other Americans. In addition, the new country’s leaders strenuously and repeatedly urged immigrants to abandon their origin countries’ prejudices; and no single religious group served as a dominant American cultural force. As well, although anti-Semitic sentiment existed, it was not codified in governmental laws and practices.

That all would suggest American audiences – Jewish or not – would not take interest in The Jew’s issues. Instead, Bannet theorizes, the play’s popularity in the States rested in its perception as a generic, comforting advocacy and confirmation of generosity and benevolence towards all immigrants being part of a shared, common “American” experience. She argues Cumberland’s desire to expose and improve the circumstances of maligned nationalities like Irish, Scots, and Jews was merely a side effect of his playwriting’s primary goal: to strengthen, maintain and assert the dominance of English culture. However, issues of cultural dominance were not as important in a post-independence America as were those of increasing unrest, unemployment, poverty and the gap between rich and poor. To Bannet, America’s first-generation immigrants of all backgrounds recognized and found themselves vindicated by Cumberland’s Sheva, who is “…poor, a stranger…” yet incredibly charitable, all while navigating an unfamiliar, increasingly tense and ever-growing society. Americans also favorably looked upon Cumberland’s emphasis on the universal applicability of Jewish tenets.

Despite — or even because of — these varying perceptions of The Jew’s messages, its many printed editions – 6 in London, 3 each in Ireland and America, in addition to German and Dutch translations – reflected its ongoing relevance. Throughout the entire 19th century, numerous reprints were issued in Great Britain and the United States – and in 1878, it was first translated into Hebrew.

-

British dramatist Richard Cumberland (1731-1811) had a religious, scholarly upbringing appropriate to his birth in the master’s lodge of Trinity College, Cambridge. His clergyman father became Bishop of Clonfert and then Bishop of Kilmore, while his mother, the daughter of a Trinity College classicist and master, was English poet John Byrom’s inspiration for the heroine of his pastoral poem Cohn and Phoebe. Richard was not the sole family member with literary talent: his youngest sister Mary became better known as poet and essayist Mary Alcock.

Cumberland was educated first at Bury St. Edmunds and then at Westminster School, where his peers included poet and satirist Charles Churchill and poet and hymnodist William Cowper. He continued his education at Trinity College, although he interrupted his fellowship there to serve as the Earl of Halifax’s private secretary.

While his dramas established Richard’s reputation, the extremely prolific Cumberland also composed several essays, a variety of prose and verse Christian writings, articles for a critical journal he edited briefly in 1809, as well as his memoirs. He was the confirmed author of 54 published and unpublished plays, nearly 1/2 of which are comedies. In those plays, Richard became renowned for questioning English prejudices about Scots, Irish, and other colonials. He tried to vindicate their good qualities, all while adhering to a strict morality and extreme patriotism. Some of his best known titles include The Banishment of Cicero, The West-Indian, The Fashionable Lover — which features Naphtali, Cumberland’s first Jewish character — and The Jew, notably original in its sympathetic presentation of a Jewish character as its hero.

-

Charles Dilly (1739-1807) was born in Southill, England into a family considered yeomen – that is, relatively wealthy, land-owning farmers regarded as of slightly lesser social standing than the landed gentry. Little more is known about Charles’ family, except that he ultimately owed his printing career to his older brother Edward. Charles had briefly went to America; upon his return, Edward invited him to join his printing and bookselling business. Subsequently, both their names appeared on the press’s books, often written by well-known figures.

The two also acquired a reputation for holding fashionable literary dinner parties. Their guests — many of whose contemporaneous memoirs recalled those soirées — included renowned authors like Samuel Johnson and Joseph Priestley; the infamous radical and politician John Wilkes; and Richard Cumberland, The Jew’s author. These parties were held at the Poultry, a street that not only merits mention on The Jew’s title page, but also has its own Jewish-related history. At one end, a prison located there until the 19th century once counted a Jewish ward among those under its jurisdiction; at the other, an area known as “Old Jewry” was used as a ghetto. In 2001, archeologists unearthed a mikveh (ritual bath-house) nearby predating the 1290 expulsion of England’s Jews.

Both Dilly brothers were considered radical publishers, with Charles acquiring the most notoriety of the two as a Dissenter – a Protestant who separated from the overwhelmingly-predominant Anglican Church; a member of the Club of Honest Whigs, an informal group of philosophers and freethinkers – Benjamin Franklin among them; and as a participant in the Society for Constitutional Information’s efforts at parliamentary reform. Charles cited his non-conformity as a Dissenter to excuse him from nomination as London’s sheriff, and also narrowly avoided a similar posting as a local alderman. Throughout, Charles remained a highly respected printer: after Edward’s death in 1779, he continued the Dilly press, and in 1803 he became master or head of the Stationer’s Company, the English printing guild. 4 years later, he died – during a visit with Richard Cumberland.

-

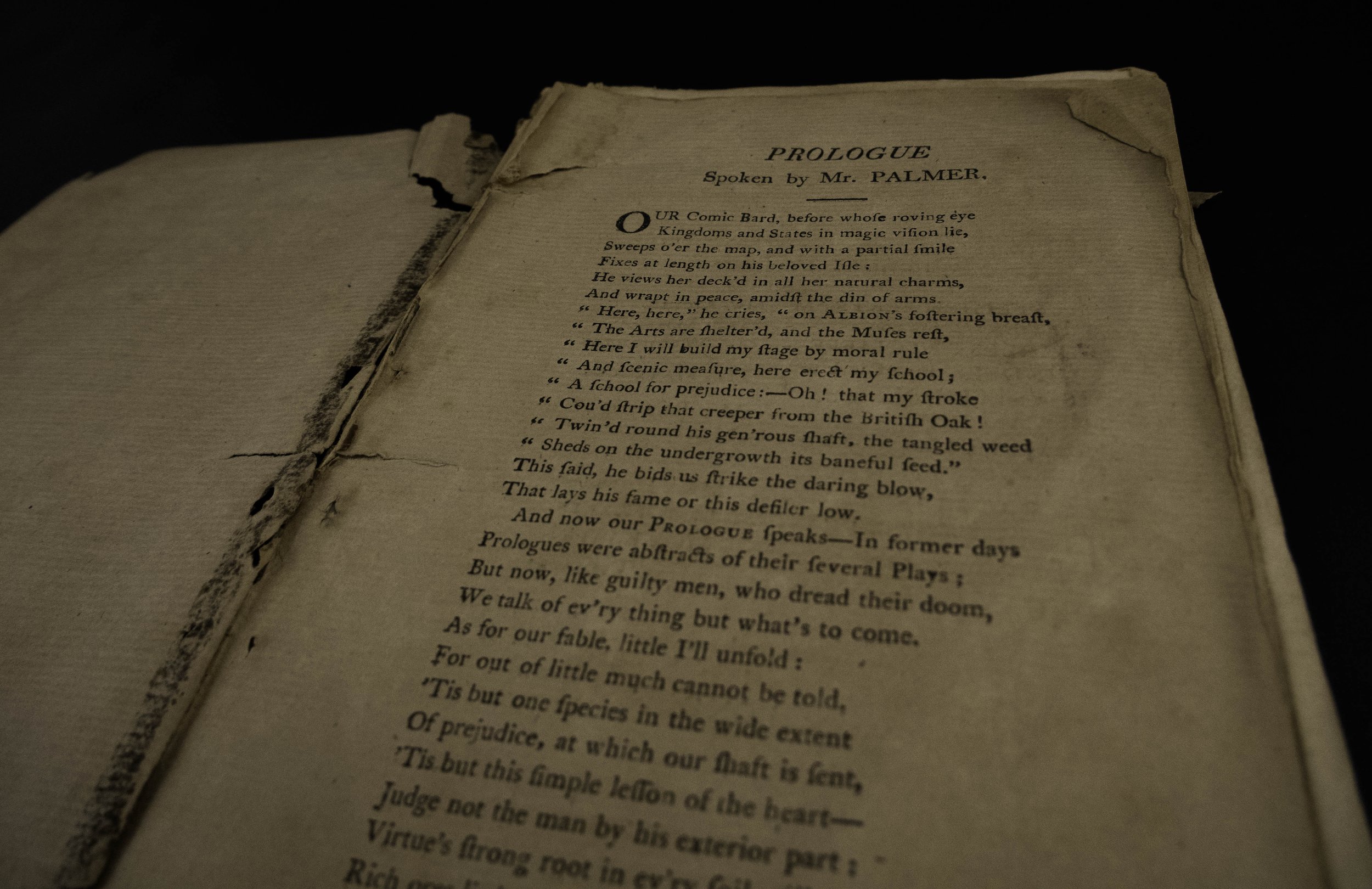

Our library’s copy of the 6th edition was printed in London in 1797. Composed of 64 leaves, it measures 21 x 13 x 1 cm and is in precarious condition. It is unclear if it originally had front or back covers – our copy has neither – and glue traces along the title page’s spine indicate it was never bound. The stitching along the spine is coming apart, and the first 3 leaves are loose. The 1st leaf, which is darker than the others, credibly suggests the book circulated without covers. Most of the leaves are in poor condition, with the text considerably faded in numerous areas. The final leaf, whose hue matches that of the first leaf, has a large tear 1/3 of the way down the spine with a portion missing measuring approximately the dimensions of a Canadian dollar coin.

However, if not for its pages’ physical condition and lack of appropriate binding, our copy could be easily mistaken for any 21st-century publication of a dramatic work: its pages’ layout feature regular margins, and letters reminiscent of a common serif font and sizing such as Times New Roman 12. On top of each leaf’s verso, “THE JEW” is printed; the top of each recto has “A COMEDY”.

The title page states: “The Jew: A Comedy. Performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. By Richard Cumberland, Esq. The sixth edition. London: Printed for C. Dilly, in the Poultry. M DEC XC VII.” Beneath this text, a small ornament again indicates this is the 6th edition. It apparently depicts a diagonally-crossed trumpet and hand harp, bounded by a leaf – possibly a fern – along its top, and a long feather along the bottom.