איך לעז

די לידער

פון מיינע פריינט

i turn to the

poems

OF MY FRIENDS

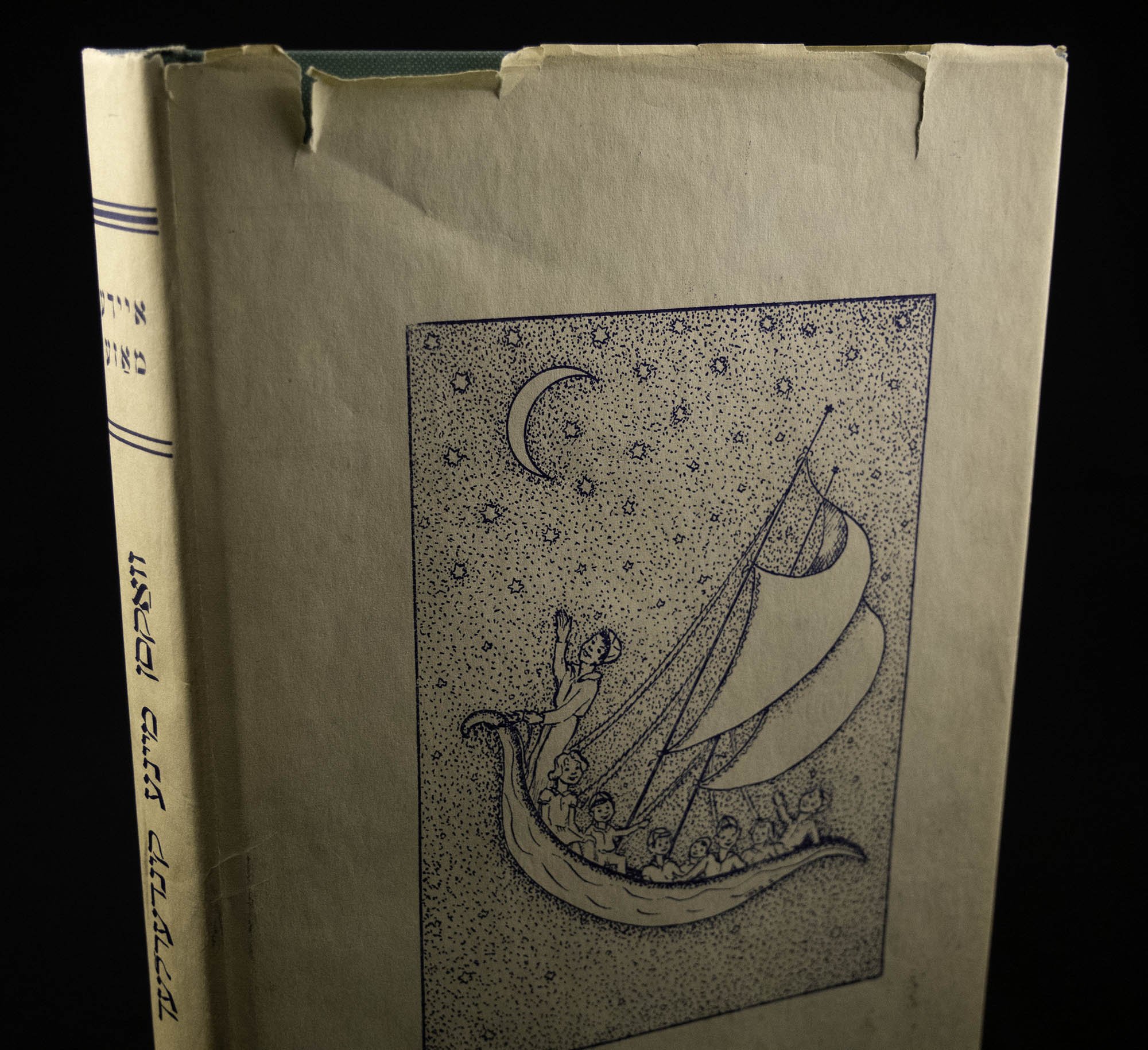

In-House Exhibition April 4, 2023 - August 1, 2023װאַקסן מײנע קינדערלעך: מוטער און קינדער-לידער, (My Children Grow: Mother and Children's Poems), ID: JC_[YL]_Maze

YIDDISH POETS OF MONTREAL

Discover the lyricism of Jacob Isaac Segal, the charm and warmth within the children’s poetry of Ida Maze, the evocative modernism of Melech Ravitch, the honest grief of Rachel Korn, and the harrowing poetic expressions of Chava Rosenfarb. Through their works, Jewish history endures through time, and allows audiences to experience Yiddish poetry at its finest.

In our exhibition “I turn to the poems of my friends”, (title from Ravitch’s poem “Child”, 1917) we are showcasing the cultural significance of the Yiddish language by featuring a few of the prominent poets that worked in Montreal throughout the 20th century, many of which were important figures at the JPL during its lifetime. These poets used Yiddish as a vehicle to connect with their greater community, both in Montreal and around to globe, while highlighting context of Jewish life, culture, and history.

Korn and Ravitch seated outside, ID: 1255_PR017723

Photograph of Saul Bellow (left), Korn (middle), and Rosenfarb (right), ID: 1255_PR007241

Portrait of young Segal (right) with unknown man, ID: 1255_PR001026

Korn speaking at a podium, ID: 1255_PR017779

Maze and Korn outside, ID: 1255_PR017724

Ravitch, Maze, Unknown, Korn, and Segal , ID: 1255_PR017727

J.I. Segal (left) and Joseph Rolnick in front of Ida Maze's house, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, c. 1940-1950, ID: 1093, J.I. Segal Fonds, Photographs

Rosenfarb presenting with Melech Ravitch and Rokhl Eisenberg Ravitch sitting beside, ID: 1255_PR006325

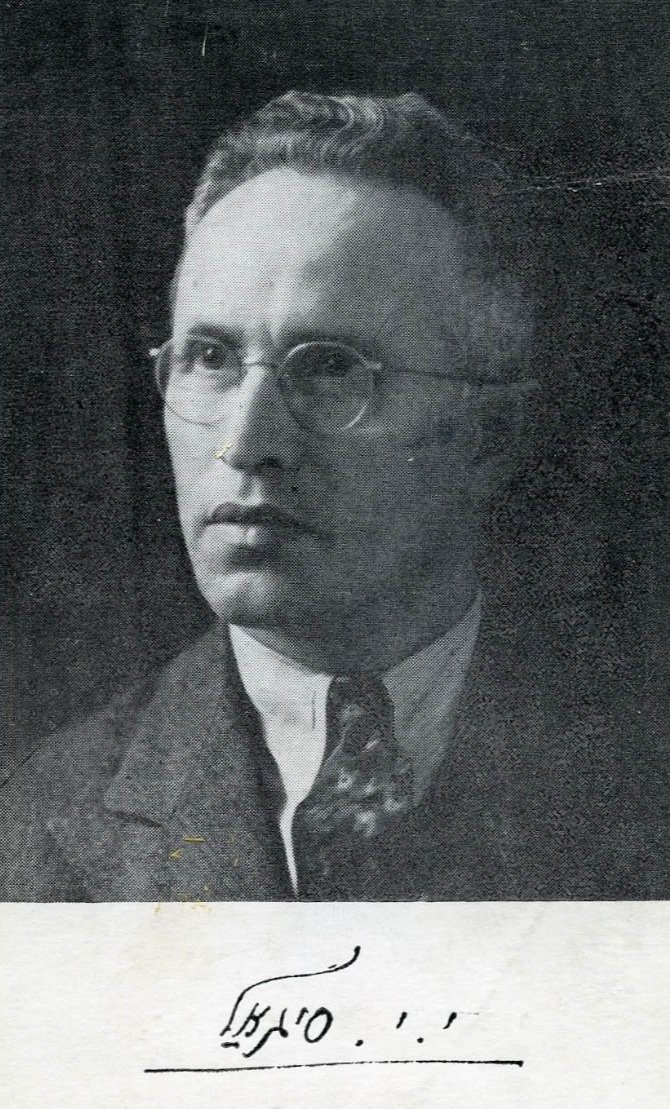

Portrait of J.I. Segal, ID: 1255_PR001025

Jacob Isaac Segal (1896-1954)

Born Yaakov Yitzchak Skolar in Slokovitz, Podolia of the Russian Empire ( modern day Solobkovtsy, Ukraine).

Segal arrived in Montreal around 1911, but it wasn’t until 1915 that he began to submit his poetry to the Keneder Adler (The Canadian Eagle), a Yiddish newspaper founded in 1907. The first poem Segal published was titled “Help” and outlined the horror of Jewish persecution that had been taking place within the Russian Empire.

These initial poems began to drum up some notoriety for Segal, and the Montreal Yiddish scene was on the edge of bursting to bloom.

Segal found true notoriety between the 1920-30’s as the burgeoning Yiddish poetry scene was gaining momentum within the community. Segal had published several books of poetry where he earned his reputation for his lyrical approach, outlining his lived experiences in bold statements, soft sentiments, and sweeping emotive phrases. Although he and his family had already moved to New York in the early 1920’s, he had made a name for himself in Montreal.

*Please note that Segal’s poems were transcribed exactly as they appear in Der Keneder Adler without diacritics.

-

Long and lazy drag the days

As I strain under my yoke

Always trolling, always struggling

My tired hands are throbbing, broke.

On the tense and drawn faces

Lies a sadness, heavy, broad.

And each pair of eyes stares blindly

With the deepest suffering.

On and on and never stopping

I stand and work at my machine.

The world requires so much clothing.

And making clothing so much blood!

— Translated by Vivian Felson

-

פון י. י. סיגאל

פויל און לאנג די טעג זיך ציען

…אין דעם יאָך בין איך געשפּאנט

,אימער, אימער פּראצען, מיהען,

.ס'ברעכט און שטעכט די מיעדע האנט

אויף די פּנימער פארצויגען

ליגט דער טרויער שווער און ברייט

און פון יעדענס שטארע אויגען

.קוקט ארויס די טיעפסטע לייד

,כ'טרייב אלץ די מאשין כסדר

…!און קיין רגע ניט גערוהט

ס'דארף די וועלט אזויפיל קליידער

…!און דער טראָסט אזויפיל בלוט

-

Brothers can you see the flames

The raging seas of blood and tears

Of those with whom you lived for years

Sharing suffering and joys.

Can you feel the great disaster,

Can you grasp the tragic fate

Of your closest friends and loved ones

How they perish, disappear.

In battle fall the strong, the sturdy

The old are driven from their homes

Betrayed by foes and Tsar and Kaiser

Women and young girls despoiled.

Jewish homes are razed and shattered

Fathers shot and stabbed and hanged

You, the only hope of orphans

Don’t stay deaf to their despair.

How can you absolve your conscience

When you let their blood be spilled,

When you do not share your morsel,

And leave them starving in the streets.

Only you can save your dear ones

Even though you’re far away.

They extend their hands and beg you:

”Save our lives as best you can!”

Save your father, mother, children

Help them, you must not delay.

Extinguish now the deadly fires

Lest we all be swept away.

— Translated by Vivian Fleson

-

יעקב יצחק םיגאל

,אה ברידער, צי זעט איהר נאך אלץ ניט דיא פלאמען

,פון בלוט און פון טרעהרען די ברויזענדע ים'ען

פון אייערע אייגענע וואס איהר האט צוזאמען

.אין ליידען און פריידען געלעבט מיט די יאהרען

צי פילט איהר נאך אלץ ניט וויא שרעקליך דער בראך איז

צי קענט איהר באגרייפען די בייזע מערכות

פון אייערע אייגענע פריינד און משפחות

…!ווי זיי קומען אום דארט און ווערען פערלארען

,אין שלאכט פאלט דער קרעפטיגער, דער שפייזער

…די אלטע פערטרייבט מען פון זייערע הייזער

דורך מסירות פון שונאים צום צאר און צום קייזער

…די עהרע פון פרויען און מיידלעך בערויבט

די אידישע היים איז צוקראכט און צובראכען

.די פאטערס געשאסען, געהאנגען, געשטאכען.

…אויף אייך נאר פערבלייבט די יתומים'ס בטחון

!…ניט בלייבט זשע צו זייער פערצווייפלונג פערטויבט

…צי וועט איהר זיי לאזען דארט ווערען צוריבען

…געפייניגט, געיאגט אומעטום און געטריבען

ניט העלפען אט יענע וואס זיינען געבליבען

…!זיך ראנגלען אין בלוטיגען שטורעם פון האס

ווי קען דען אייך ריין בלייבען דער געוויסען

,ווען איהר וועט ניט טהיילען מיט זיי אייער ביסען

,און לאזען עס זאל זיך דאס בלוט פערגיסען

…!זיי זאלען פון הונגער דארט פאלען אין גאס

נאר איהר קענט זיי העלפען, ניט לאזען צוטרעטען

!איהר נאענטע ווייטע... נאר איהר דארפט זיי רעטען

:זיי שטרעקען צו אייך די הענד און זיי בעטען

"!ערהאלט אונזער לעבען מיט וואס נאר איהר קענט"

רעטעט דעם טאטען שיקט הילף דער מאמען

,קינדערלעך! העלפט, איהר טארט ניט פארזאמען

לעשט אויס די שרעקליכע פלאמען

“!אז ניט וועלען מיר אלע דא ווערען פערברענט

Portrait of Ida Maze, ID: 1255_PR05158

ida maze (1893-1962)

Born Ida Zhukovsky in the Belorussian village of Ugli. At the age of 12, she and her family settled in Montreal where she began writing poetry. However, it wasn’t until Maze was 33 when she published her first volume of poetry titled A mame (A mother) following the death of her eldest son Bernard in 1923.

Maze’s poetry often draws upon the influence of family, gathering, and togetherness while calling on inspiration gained from the sentiments, ideals, and memories of generations gone by. Fellow poets and writers would often describe her work as playful and childlike, but also tender and motherly too—and these qualities were not only reserved for her poetry, but also for many within the Jewish community of Montreal in which Maze served as a mentor, helper, comforter, and encourager. Maze’s home often served as a place of gathering for family, friends, and those needing a warm hearth, food, and bed. Maze’s house on Esplanade Avenue was known throughout the Jewish community near and far, where Maze would host literary salons, poetry readings for children, and a number of other artists, musicians and writers.. Maze was a pillar of her community, and was dedicated to the many that crossed the threshold of her doorway as well as the whimsical, loving, and playful poetry she wrote.

-

If I were you,

And you were me,

Then I would

Wear your shoes.

I would be eight,

And you would be four;

Then would you

Play with me?

— Translated by Miriam Udel

-

אַז איך װאָלט זײַן דו

,און דו וואָלסט זײַן איך

וואָלט איך – ג

.עטראָגן דײַנע שיך

,מיר וואָלט זײַן אַכט יאָר

;און דיר װאָלט זײַן פֿיר

– וואָלסטו דאַן

?געשפּילט זיך מיט מיר

-

Somewhere very far away,

Where wagons will not go —

There stands a little cottage

As it’s stood for years, just so.

Sitting quiet and abandoned

Doors and shutters bolted shut,

Days and years pass; only wind blows

Through the chimney of the hut.

Everybody’s known for years:

Its people all have gone away

Only wind blows in the chimney

Not a soul has come to stay.

One night when all are sleeping,

And the wind is sleeping too —

Lights come on inside the cottage

And smoke wafts up the flue.

Door and shutter are unbolted.

In a corner, by a light,

Sits a grandpa learning Torah;

A child listens with delight

To Grandpa’s tales of wonder-beams,

Absorbs them through her dreams.

Hard by the hearth, a spinning wheel;

From silken thread, so thin and soft,

Grandma spins her lovely stories

And, with the smoke, sends them aloft.

The smoke takes up the grandma’s stories,

Repeats them to a wind beguiled —

On its wings the wind will spread them,

Giving some to every child.

— Translated by Miriam Udel

-

,ערגעץ ווייט, ערגעץ ווייט

,ניט מיט פורן צו דערפאָרן

,שטייט אַ הייזעלע אַ קליינס

.שוין פון פילע לאַנגע יאָרן

– טיר און לאָדן אויפן ריגל

,שטיל דאָס הייזל און פאַרלאָזן

– דורך די טעג און דורך די יאָרן

.נאָר אין קוימען ווינטן בלאָזן

,ווייסן אַלע שוין פון יאָרן

,אַז דאָס הייזל איז פאַרלאָזן

,און אַז וווינען, וווינט דאָרט קיינער

.נאָר אין קוימען ווינטן בלאָזן

,טרעפט אַ נאַכט, ווען אַלע שלאָפן

,און די ווינטן שלאָפן אויכעט

,ווערט אין יענעם הייזל ליכטיק

.און פון קוימען דאָרטן רויכערט

– טיר און לאָדן אויפגעריגלט

,אין אַ ווינקל ביי אַ שיין

,זיצט אַ זיידע לערנט תורה

זיצט אַ קינד און הערט זיך איין

,צו דעם זיידנס ווונדער-מעשיות

.און חלומט זיי אין זיך אַריין

,ביי אַ קוימען, ביי אַ שפּין-ראָד

,פון זייד די פעדים, דין און ווייך

,שפּינט אַ באָבע שיינע מעשיות

.און צעשיקט זיי מיטן רויך

נעמט דער רויך דער באָָבעס מעשיות

– גיט זיי איבער צו דעם ווינט

צעשפּרייט דער ווינט זיי אויף זיינע פליגלען

.און טיילט זיי אויס צו יעדן קינד

Portrait of Melech Ravitch, ID: 1255_PR000874

melech ravitch (1893-1976)

Melech Ravitch was the pen name of Austrio-Hungarian poet Zechariah Choneh Bergner. Ravitch first began writing poetry as a part of the Yiddishist movement that promoted Yiddish language and culture in Eastern Europe at the turn of the 20th century. However, Ravitch emigrated to Australia in 1935 before eventually settling in Montreal, in 1938 where he participated in the Yiddish literary scene.

Ravitch was already a well-established writer and poet before he emigrated to Montreal, having written and published his first set of poems in 1910 at 17 years old while living in Galicia (now Poland). Ravitch’s work had different periods of influence, taking more of a modernist tone and structure during the 1920’s and 30’s, with strong influence from American poet Walt Whitman, while his poetry after 1950 often sought to look back at his life, pondering more on the metaphysical and spiritual, featuring the memories of his own personal journey. Ravitch had a long and fruitful career as a poet and writer, and has a prolific selection of work to explore.

-

So early this autumn evening

My rooms grow cold.

Lighting a candle

I turn to the poems of my friends.

All of the sudden, a knock!

—Oh, it’s you—

But he brushes past to a char.

He snuffs out the light.

Outside the darkness has deepened.

“What good is a wife to you—” he begins,

”To has a child who‘ll be sick…

Those bones are so small

And if he laughs now and then

that too makes me uneasy.

So little—how can you leave him alone

even for a minute!

He’ll fall from the table—blood flows

So easily from such a small blonde head.

If it’s chilly at night you mumble about fever.

You want to tear at your own skin

At the anguish of rising temperature—

And if suddenly the little heart stops

—it’s all over…”

He was yellow as parchment

The funeral clothes were tiny—

The shroud so shrunken—

1917

— Translated by Seymour Mayne and Rivka Augenfeld

-

אין אַן אָסיען-פאַרנאַכט

שוין קיל און בין-השמשותדיק אין מיינע שטיבער

.צינד איך אָן אַ ליכט, און לעז די לידער פון מיינע פריינט

.קלאַפּט עמעץ אָן, גיי איך און עפן

!אָ, דו מיין ליבער —

,ער אָבער זעצט זיך אַקעגנאיבער

;שפּאַרט אָן דעם קאָפּ אָן ביידע הענט

.בלאָזט אויס דאָס ליכט

.דערוויילע איז געוואָרן טיפע פינסטערניש

,דו, זאָגט ער —

,וואָס האָט דיר אַ ווייב געטויגט

?אַז זי זאָל האָבן דיר אַ קינד אַ קראַנקס

;עס איז דאָך קראַנק, זיינע ביינדאַלעך זענען אזוי שמאָל

און אַז עס לאַכט שוין יאָ אַמאָל, אַמאָל

…געפעלט מיר נישט זיין לאַכן

אָט אַזאַ קליינס,לאָז עס נאָר איבער אויף איין מינוט

,אויף אַ טיש, פאַלט עס אַראָפּ

,און אָט פון דעם קליינעם, בלאָנדן קאָפּ

.קאָן גיין אַ גאַנצער בעקן בלוט

,און טאָמער פאַרקילט זיך עס, אָט אַזאַ קליינס

?קען עס דען אויסהאַלטן פערציק גראַד היץ

— איין טאָג, אפשר

,ביינאַכט וועט עס דיר רעדן פון פיבער

— וועסט רייסן די הויט פון דיין לייב דיר פאַר צער

— און פּלוצלונג בלייבט דאָס הערצעלע שטיין

,איז אַלץ אַריבער

;אָט אַזאַ קליינס ווערט באַלד ווי פּאַרמעט געל

— און די תכריכימלעך

— די גאַנץ קליינענקע תכריכימלעך

1917

-

In the garden. Summer's end. Evening. On a bench.

The second highest tower burns in the west.

The night wind has risen and with the rake

I begin to compose a poem in the sand:

We are destructive, and friends' blood

is as thin as water to us.

Can I ask God or man why this is so?

It seems relatively easy to be good.

Like the slaughterer's knife

we are always in the right.

I ask you again, God or man.

It seems so difficult to fully give way to strife.

We destroy, but who else sings on

about turning the other cheek to the oppressor--

And under our jackets we can hardly hide

the newly acquired weapon.

In the garden. Summer's end. Evening. I rise from the bench

The darkness has eclipsed the last of the towers.

I simply say farewell to the emptiness

and in the darkness trample on my poem written in the sand.

1957

— Translated by Seymour Mayne and Rivka Augenfeld

-

.אין גאָרטן. סוף-זומער. פֿאַרנאַכט. אויף אַ באַנק

.אַ לעצט-העכסטער טורעם אין מערב-זײט פלאַמט

עס שׂטאַרקט זיך דער נאַכט-װינט. און איך שׂרײב אַ ליד

:מיט אַ ריטל, אַטרוקנס אין גאָרטן-זאַמר

שלעכט בֿיסטו מענטש און הפּקר װי װאַסער

.איז דיר דײן חברס װאַרעם בלוט

?גאָט מײנער, מענטש מײנער, זאָג מיר — פאַרװאָס

!עס איז דאָך אַזוי גרינג צו זײן גוט

,שלעכט ביסטו מענטש, װי א חלף דײן געשרײ

!אַז דו ביסט אײביק גערעכט און גערעכט

?גאָט מײנער, מענטש מײנער, זאָג מיר — פאַרװאָס

!עס איז דאָך אַזוי שװער צו זײן שלעכט

,שלעכט ביסטו מענטש, און דאָך זינגסטו צו גאָט,

— פּון דערלאַנגען דעם שלעגער די אַנדערע באַק

,אָבער אונטער דער פּאָלע, גאַנץ װײניק פּאַרבאָרגן

.האַלטסטו אַ נאָר-װאָס געשאַרפטע האַק

.אין גאָרטן. סוף-זומער. פאַרנאַכט. פּון דער באַנק שטײ איך אויף

.דער לעצט-העכסטער טורעם -- שוין אַפּגעפלאַמט

!זאָג איך סתם אין דער פּוסטקײט אַרײן: גוטע נאָכט

.און צעטרעט אין דער פּינצטער מײן ליד אינעם זאַמר

1957, אַפּריל

![טויג ציקלוס, poetry anthology featuring Ravitch and signed by him, 1969, ID: JC_[YL]_Ravitch](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/c92718ff-145c-4cd4-b778-ba848014dc0e/JC_%5BYL%5D_Ravitch_1.jpg)

טויג ציקלוס, poetry anthology featuring Ravitch and signed by him, 1969, ID: JC_[YL]_Ravitch

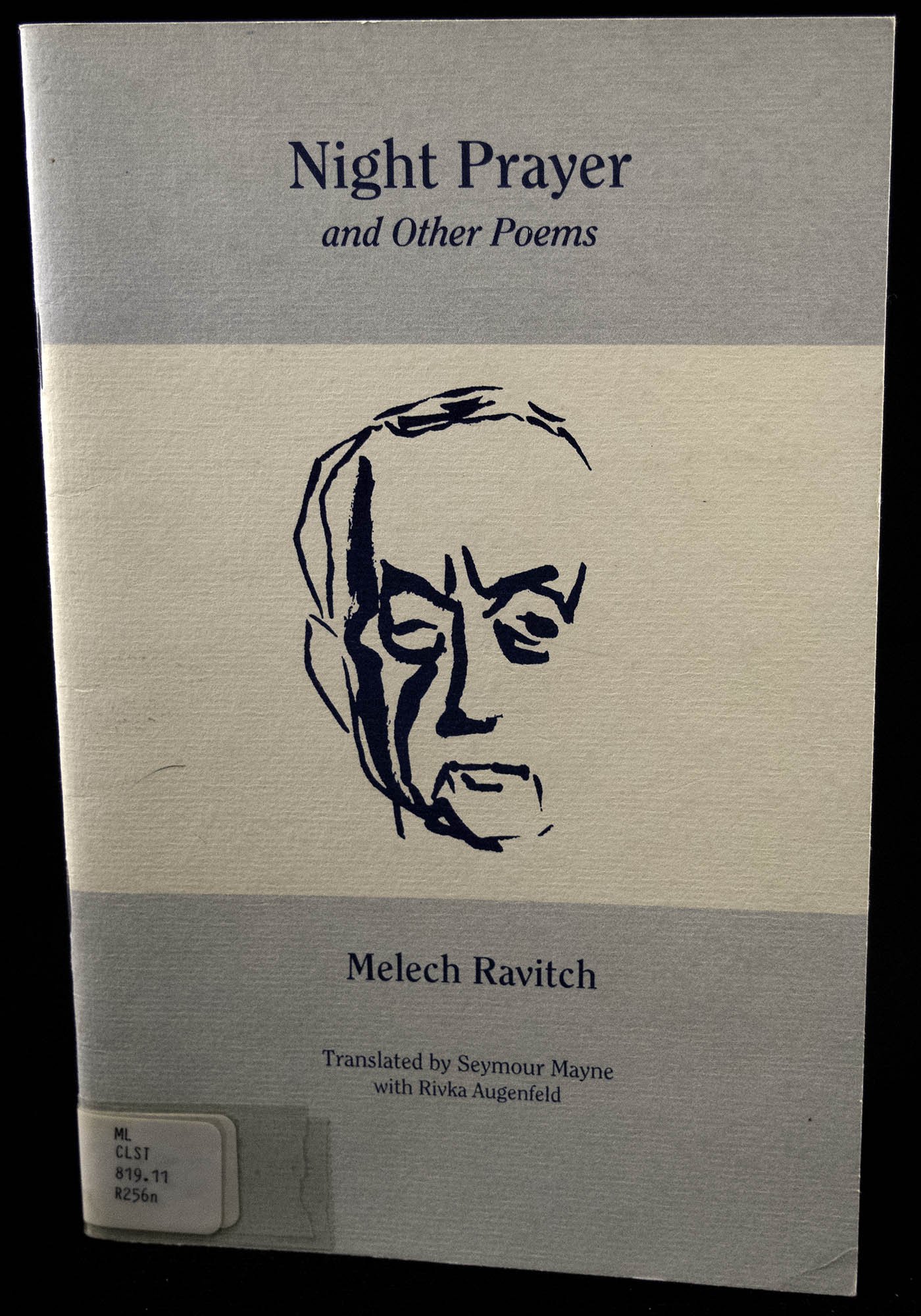

"Night Prayer" by Ravitch, ID: JC_MLCLST_819.11R256n

![װאַקסן מײנע קינדערלעך: מוטער און קינדער-לידער, ID: JC_[YL]_Maze](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/6d076c35-16d8-4ffe-9e57-f6bad3322a94/JC_%5BYL%5D_Maze_1.jpg)

װאַקסן מײנע קינדערלעך: מוטער און קינדער-לידער, ID: JC_[YL]_Maze

![Text: Chava Rosenfarb, װו ביסטו, זונענין? , Composer: מוזיק: יצחק הײלמאן, ID: JC_[YL]_Rosenfarb, Chava](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/1a0e7d91-60fc-4f42-8e46-1e02eb7a1e3d/JC_%5BYL%5D_Rosenfarb_Chava_2.jpg)

Text: Chava Rosenfarb, װו ביסטו, זונענין? , Composer: מוזיק: יצחק הײלמאן, ID: JC_[YL]_Rosenfarb, Chava

Illustrated portrait of Ravitch, ID: 1255_PR000872

!["Verses in the Sand" in English and Yiddish from "Night Prayer", ID: JC_[YL]_Ravitch](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/1dc3b16a-21ec-4c96-9d08-6373a79b5857/JC_%5BYL%5D_Ravitch_4.jpg)

"Verses in the Sand" in English and Yiddish from "Night Prayer", ID: JC_[YL]_Ravitch

![װאַקסן מײנע קינדערלעך: מוטער און קינדער-לידער, ID: JC_[YL]_Maze](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/f3d61390-2f28-4394-b1c8-9ceb7079757b/Maze_GrowingUp.jpg)

װאַקסן מײנע קינדערלעך: מוטער און קינדער-לידער, ID: JC_[YL]_Maze

!["International Poetry Quarterly, Bitterroot, Tenth Anniversary", Summer 1972, featuring poetry by Korn, ID: JC_[YL]_Korn](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/d46b306a-19cf-4908-8b9a-a455f8f55324/JC_%5BYL%5D_Korn_3.jpg)

"International Poetry Quarterly, Bitterroot, Tenth Anniversary", Summer 1972, featuring poetry by Korn, ID: JC_[YL]_Korn

![Illustrated portrait of Segal featured in יובילי סואװעניר, ID: JC_[YL]_Segal_J](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/1db3a210-0e41-41c3-9dec-320a893aa197/JC_%5BYL%5D_Segal_J_2.jpg)

Illustrated portrait of Segal featured in יובילי סואװעניר, ID: JC_[YL]_Segal_J

Illustrated portrait of Korn, ID: 1255_PR000837

![Advert for a lecture with Rosenfarb at the JPL, October, 2004, ID: 1000_[1448]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/8a508053-b573-4711-a235-88cb9d93911b/1000_%5B01448%5D_1.jpg)

Advert for a lecture with Rosenfarb at the JPL, October, 2004, ID: 1000_[1448]

![רויטער מאָן by Korn, ID: JC_[YL]_Korn](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/2dc95a75-bf66-47eb-8bd1-e1707150b3d2/JC_%5BYL%5D_Korn_1.jpg)

רויטער מאָן by Korn, ID: JC_[YL]_Korn

![יובילי סואװעניר (brown) and 2 copies of נױאנסן: מאָנאַטשריפט פאר לידער, מיניאטורען און עסײס (for which Segal was the editor), 1921, ID: JC_[YL]_Segal_J](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/66990081-8f00-42db-8f15-150818088b40/JC_%5BYL%5D_Segal_J_1.jpg)

יובילי סואװעניר (brown) and 2 copies of נױאנסן: מאָנאַטשריפט פאר לידער, מיניאטורען און עסײס (for which Segal was the editor), 1921, ID: JC_[YL]_Segal_J

![Illustrated portrait of Maze by Rita Briansky, ID: 1291_[8]_72](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/61895e2e-8df4-4aa4-b2a3-9abea8edfb9c/1291_%5B8%5D_72_Maze.jpg)

Illustrated portrait of Maze by Rita Briansky, ID: 1291_[8]_72

![לידער און ערד, featuring Korn's poetry and prose, ID: JC_[YL]_Korn](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/ea022e23-91f5-4ffb-b594-4d131e46d950/JC_%5BYL%5D_Korn_2.jpg)

לידער און ערד, featuring Korn's poetry and prose, ID: JC_[YL]_Korn

Portrait of Rachel Korn, ID: 1255_017749

rachel korn (1898-1982)

Born in Podliszki, Galicia, (now Poland) and emigrated to Montreal, Canada in 1948 at the age of 50. Korn first published her poetry after returning to Poland from Moscow following the end of the first World War in 1918. Yiddish had not been the initial language Korn composed in, and she instead had been writing in her native Polish at the beginning of her career. However, she later decided to write in Yiddish after her husband introduced her to the language, finding great joy in its use for her poetry in comparison to Polish, which she felt had become marred with anti-semitic sentiment.

Korn’s poetry offers her own personal expression of the grief and struggle she faced while living through both world wars and the subsequent evacuation of Poland by the Russians during the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union. Korn’s poetry evokes a deeply lonely and longing narrative voice—a voice which often speaks to the darkness of circumstance of her life, and the grief and loss she underwent throughout the trials of two world wars.

Sponsored by Ida Maze, Korn emigrated to Montreal and was welcomed into the Montreal poetry scene immediately, finding a wealth of camaraderie. It was in this setting where she would continue to write and publish poetry in Montreal until her death in 1982.

To learn more about the life and work of Rachel Korn, we invite you to visit the JPL-A’s in-depth exhibition here.

-

How you’ve shamed me

In your sight—

From the height

Where the word renewed creation

You’ve flung me down

Into a dungeon without windows or light,

Where everything is wrongside-out

And freak thoughts

Lurk,

Drunk on the milk

Of green poppies.

Made me a citizen

Of a landscape

Imagined by Satan.

A landscape

That can never be my home.

Even memory

Is drown in tears

In this place.

No one hears me calling,

Not even you, Lord,

You’ve hidden your face

Behind a hem of extinguished stars.

— Translated by Seymour Levitan

-

ווי האָסטו מיך פאַרשעמט

– פאַר דיין אייגן אָנגעזיכט

,פון יענער הייך,

וווּ דאָס וואָרט צעעפנט אַ נייעם בראשית

האָסטו מיך אַראָפּגעשליידערט

אין אַ קאַרצער

,אָן פענסטער, אָן ליכט

וווּ אַלץ איז קאַפּויער

און ס'ליגט אויף דער לויער

שגעון

אָנגעשיכורט מיט דער מילך

.פון גרינע קעפּלאך מאָן

האָסט מיך געמאַכט פאַר אַ בירגערין

פון אַ לאַנדשאַפט

,אויסגעטראַכט פון שטן אַליין

,אַ לאַנדשאַפט

,וואָס קען קיין מאָל נישט ווערן מיין היים

,אַ לאַנדשאַפט

וווּ אַפילו דערמאָנוג

– ווערט דערטראָנקען אין אַ מבול פון טרערן

,פון דאַנען קען קיינער מיין רוף נישט דערהערן

,אפילו נישט דו, מיין האַר

וואָס פאַרשטעלסט דיר דיין פּנים

.מיטן זוים פון פאַרלאָשענע שטערן

-

On the other side of the poem there is an orchard,

and in the orchard, a house with a roof of straw,

and three pine trees,

three watchmen who never speak, standing guard.

On the other side of the poem there is a bird,

yellow brown with a red breast,

and every winter he returns

and hangs like a bud in the naked bush.

On the other side of the poem there is a path

as thin as a hairline cut,

and someone lost in time

is treading the path barefoot, without a sound.

On the other side of the poem amazing things may happen,

even on this overcast day,

this wounded hour

that breathes its fevered longing in the windowpane.

On the other side of the poem my mother may appear

and stand in the doorway for a while lost in thought

and then call me home as she used to call me home long ago:

Enough play, Rokhl. Don’t you see it’s night?

— Translated by Seymour Levitan

-

פון יענער זייט ליד איז אַ סאָד פאַראַן

און אין סאָד איז אַ הויז מיט אַ שטרויענעם דאַך

,עס שטייען דריי סאָסנעס און שווייגן זיך אויס

.דריי שומרים אויף שטענדיקער וואַך

,פון יענער זייט ליד איז אַ פויגל פאַראַן

,אַ פויגל ברוין־געל מיט אַ רויטלעכן ברוסט

ער קומט דאָרט צו־פליען יעדן ווינטער אויפסניי

.און הענגט ווי אַ קנאָספּ אויף דעם נאַקעטן קוסט

,פון יענער זייט ליד איז אַ סטעזשקע פאַראַן

,אַזוי שמאָל און שאַרף, ווי דער דין־דינסטער שניט

,און עמעץ, וואָס האָט זיך פאַרבלאָנזשעט אין צייט

.גייט דאָרט אום מיט שטילע און באָרוועסע טריט

פון יענער זייט ליד קענען וואונדער געשען

,נאָך היינט, אין אַ טאָג, וואָס איז כמאַרנע און גראָ

ווען ער דופקט אַריין אין דעם גלאָז פון דער שויב

.די צעפיבערטע בענקשאַפט פון אַ וואונדיקער שעה

,פון יענער זייט ליד קען מיין מאַמע אַרויס

און שטיין אויף דער שוועל אַ וויילע פאַרטראכט

און מיך רופן אַהיים, ווי אַמאָל, ווי אַמאָל׃

.גענוג זיך געשפּילט שוין. דו זעסט נישט? ס’איז נאַכט

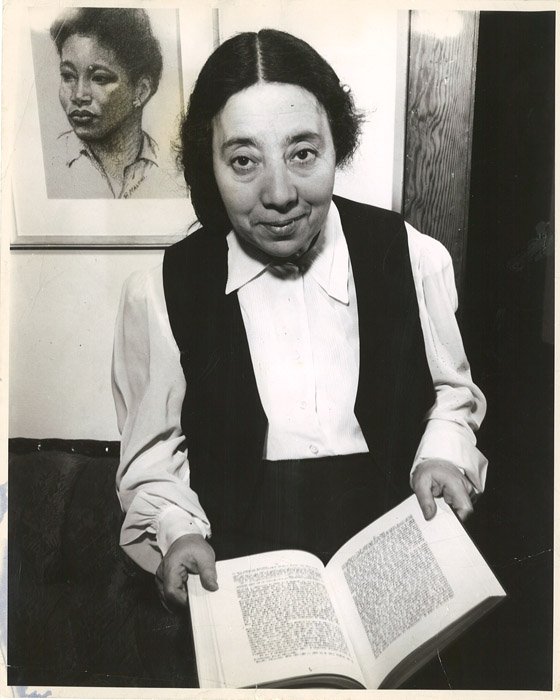

Portrait of Chava Rosenfarb, ID: 1255_PR000633

chava rosenfarb (1923-2011)

Born in Lodz, Poland a decade before the outbreak of the second World War. Sometime between 1939 and 1940, Rosenfarb and her family were sent to the Lodz Ghetto before being deported to Auschwitz, where she was separated from her father and then moved to Bergen-Belson concentration camp. After the liberation of Bergen-Belsen in 1945, Rosenfarb would live in Belgium for 4 years before emigrating to Montreal, Canada with her husband, Henry Morgantaler.

Rosenfarb began writing poetry as a teenager, and continued to compose poetry after her liberation and subsequent emigration to Montreal, and published her first collection in 1947. However, in 1972 Rosenfarb transitioned from poetry to prose after finding that she couldn’t express the horror, grief, and pain she experienced during the Holocaust within the parameters of poetic or dramatic writing—instead Rosenfarb opted to publish a chronicle of her experiences in a three volume set of books titled The Tree of Life that details the destruction of the Lodz Jewish community. Rosenfarb’s poetry and prose breathes out a voice of sharp honesty, romance, deep longing, and subtle appreciation of the complexities in life, even within dire and harrowing circumstances.

-

Praise likewise the day

standing still as a water—

a mirror without a reflection.

Though hours that glide

through its hazy-pale surface

like breath-carried skaters

are shunning the lighted eye of awareness,

erasing their footprints

before they are falling—

Praise likewise that day

you will never remember.

Praise likewise that day

whose name is a riddle

and you are not sure,

is it now, is it later?

And all the accounts

with yourself and with others

are resting hidden

in white and gray sponges;

and words that you utter

and words that you ponder

resemble the minnows

that fall through ripped net-holes

deep into the silence …

Praise likewise that day

when you feel no discomfort

of soul or of body;

when moving your limbs

you don’t feel their burden

and you don’t hear the pulse

of time in your bosom;

and throughout your mind

reflections are swimming

like gossamer threads

without knots or connections—

not bound and not torn …

Praise likewise that day

when no letters are coming,

no tidings arriving,

not good ones, not bad ones—

when silent the bell at your door

and the telephone’s quiet;

and the loudest of echoes

that reaches your being

is that of a kiss

that your baby gives you

with lips sweet as honey …

When the light is down

and the end is approaching

and sudden at last

you find yourself standing

in a gate of deep darkness;

look once more behind you

to that bubble of being—

and praise it, that day

that drips out of existence,

dissolving unnoticed

in the night of oblivion.

— Translated by Chava Rosenfarb

-

,זאָלסט לויבן דעם טאָג

— וואָס איז ווי אַ שטייענדיק וואַסער

.אַ שפּיגל אָן אָפּשײַן

כאָטש שעהן, וואָס גליטשן

,דורך אים זיך אַריבער

ווי וואָגלאָזע גליטשערס געהילטע אין אָטעמס

,פאַרמײַדן דאָס ליכטיקע אויג פוּן זכרון

פאַרווישנדיק שפּורן

- - - נאָך איידער זיי פאַלן

,זאָלסט לויבן דעם טאָג

.וואָס דו וועסט אים קיינמאָל ניט געדענקען

,זאָלסט לויבן דעם טאָג

וואָס דו פרעגסט זיך זײַן נאָמען

,און ווייסט ניט גענוי

צי ס'איז הײַנט, צי ס'איז נעכטן

און אַלע חשבונות מיט זיך און מיט יענעם

,שלאָפן פאַרמעקטע אין גרוי-ווייסע שוואָמען

און ווערטער געזאָגטע

און ווערטער געהערטע

זײַנען ווי פישלעך

וואָס פאַלן אַדורך דורך צעדריוולטע נעצן

.אַרײַן אין דער שטומקייט

,זאָלסט לויבן דעם טאָג

ווען עס טוט דיך ניט קוועלן

,ניט גוף, ניט נשמה

ווען רירסט דײַנע גלידער

און וועגסט זייער לאסט ניט

און הערסט ניט דעם דופק

פון צייט אין דיין בוזעם

און ס'שווימען פארביי

,פאר דיין מוח מחשבות

– וואָס זיינען ווי פעדים, וואָס האָבן קיין קנופּן

.ניט גאנץ, ניט צעריסן

,זאָלסט לויבן דעם טאָג

.ווען עס קומען קיין בריוו ניט

,ווען הערסט ניט קיין בשורות

.ניט גוטע, ניט שלעכטע

ווען ס'קלינגט ניט דער גלאָק ביי דער טיר

און דער טעלעפאָן שווייגט

און דער הילכיקסטער עכאָ, וואָס גרייכט צו דיין וועזן

,איז דער פון א קוש

וואָס עס גיט דיר דיין קינד

.מיט פרישע, מיט טוי-פייכטע ליפּן

ווען ס'טיקט זיך דאָס ליכט

און עס פאלט צו דער סוף

און אין איין מיטאמאָל

דערזעסטו זיך שטיין

– אין א טיף, טונקל טויער

קוק נאָך איינמאָל צוריק

צו דעם בלעזעלע וואָר

,און לויב אים, דעם טאָג

וואָס רינט אויס פונעם זיין

אומבאמערקט און פארשווינדט

.אין דער נאכט פון פארגעסן

-

For the ruins of the Lodz Ghetto

From the depths I call you,

Song of home interrupted…

There, amid rotten fences and blind holes

You trace your own tracks,

Like a stray dog.

Along shingles of scattered roofs, you rove,

Like a spider, alone

On the gray web of her generation.

There, you weep into a dried-up well

Like a child, gasping

At a mother’s stricken breast.

From inside a fallen chimney, you wail

Lamenting, abandoned

—a graveyard’s wind.

There, you cry into windows stripped of glass,

Like an autumn fly

In its dying shiver.

Amid stone ruins, you sway with the grass,

Like the soul over a grave

Like the Shekhina over a cradle, you hover.

You, holy song of ruined home

You wander the streets, empty, bereft

And you call from every rag, from every stone

Your mute call, mimaamakim, from the depths.

Right there, I see you on Mlinarski Street, Marishiner

How you, in dry earth, wither with the thorn.

You used to grow in the garden plot, the botvine

Turning red to green before every door.

And while slender onions grew there,

Potato patches smiled in bloom.

There a ghetto woman did her weeding,

And a ghetto man, with a watering can, strode through.

And birds never sang so sweetly

As there, perched on a thin branch.

Hope never grew so greenly

As on a crooked ghetto-patch.

And though the heavens hung above

Surrounded by rifles and rusted rods,

Nowhere else had life held such purpose

And no one had ever felt so close to God.

— Translated by Hannah Pollin-Galay

-

.צו די חורבֿות פֿון לאָדזשער געטאָ

,פֿון די טיפֿענישן רוף איך דיך,

... ליד פֿון פֿאַרשניטענער הײם

דאָרט צװישן צעפֿױלטע פּלױטן און בלינדע לעכער

,זוכסטו דײַן אײגענעם שפּור

.װי אַ פֿאַרבלאָנקעטער הונט

און הױדעסט זיך אױף ברעטער פֿון צעשיטע דעכער

— װי אױף אַשיקן געװעב פֿון איר דור

.אַן אײנזאַמע שפּין

,דאָרט װײנסטו אַרײַן אין אַ פֿאַרטרוקנטן ברונעם

— װי אױף אַ מאַמעס טױטער ברוסט

.אַ לעכצנדיק קינד

און יאָמערסט אַרױס פֿון אַ צעפֿאַלענעם קױמען

,אַזױ קלאָגעדיק און װיסט

.װי אַ בית־עולמדיקער װינט

,דאָרט קלימפּערסטו אין נאַקעט־צעשפּאָלטענע שױבן

— װי אין אומקום־געציטער

.אַ האַרבסטיקע פֿליג

,און הױדעסט זיך מיט גראָזן אױף חרובֿע שטײנער

װי די נשמה איבער אַ קבֿר

— — — — — — — — — — —

.װי די שכינה איבער אַ װיג

דו הײליק ליד פֿון חרובֿער הײם

דאָרט װאָגלסטו דורך גאַסן װיסט און נאַקעט

און רופֿסט פֿון יעדער שמאַטע, יעדער שטײן

.דײַן שטום גערוף פֿון ממעמקים

אָט זע איך דיך דאָרט אױף מלינאַרסקע, מאַרישינער

.װי דאַרסט מיט אַ דאָרן אין טרוקענער ערד

,אַמאָל ביסטו דאָרט אױפֿגעגאַנגען מיט דער באָטװינע

.װאָס האָט זיך רױט געגרינט פֿאַר יעדער שװעל

,און אױפֿגעגאַנגען איז דאָרט ציטריק דינע ציבעלע

,און קאַרטאָפֿל־בײטן האָבן שמײכלענדיק געבליט

און װילדגראָז האָט גערײניקט דאָרט אַ געטאָ ייִדענע

.און מיט אַ קענדל װאַסער האָט געשפּאַנט אַ געטאָ־איד

און פֿײגל האָבן קײנמאָל שענער נישט געזונגען,

װי דאָרטן אױף אַ דאַרער צװײַג.

ס׳איז קײנמאָל האָפֿענונג אַזױ גרין נישט אױפֿגעגאַנגען,

װי אױף אַ הױקערדיקער געטאָ־בײט.

,און כאָטש געהאָנגען איז דער הימל אױבן

,אַרומגעזײמט מיט קאָלבעס און מיט זשאַװער דראָט

דאָך האָט אין ערגעץ אַזאַ טעם געהאַט דאָס לעבן

.און פֿאַר קײנעם אַזױ נאָענט געװען איז גאָט

"Praise" handwritten Yiddish with Chava's English translation from "Prism International V. 5 #2", Autumn 1965, ID: JC_[YL]_Rosenfarb

Celebration of Life, "Ida Massey - The Person" written by Rita Brianksy and from "The Canadian Jewish Chronicle", June 14, 1963, ID: 1291_[18]_3

Photograph of Rachel Korn with inscription by A.G. Monmart: "If, with those sufferings in mind, you forced yourself to resignation and forgiveness, Lift up your chin! Tears will no longer glide down; they will illuminate your face. To Rachel KORN, in all admiration. A.G. MONMART, 23II67, ID: 1255_PR017776

Article "Writer Rosenfarb welcomed back to Montreal", from "The Canadian Jewish News", April, 2004, ID: JC_[YL]_Rosenfarb

Article "Melech Ravitch, 70" from the "Congress Bulletin", December, 1963, ID: JC_[YL]_Ravitch

Interior, group portrait of the staff of the Keneder Adler and Canadian Jewish Chronicle. Back row, l to r: Israel Medres, AM Klein, Mordecai Ginsburg, J. Gallay, J.I. Segal, Melech Ravitch, N.J. Gottleib, Mrs. Chana Widerman. Front row, l to r: Leon Crestohl, Dr. A. Stilman, Max Wolofsky, Israel Rabinovitch, Hirsch Wolofsky, B.G. Sack, Halpern., ID: 1255_PR01076

learn more about these poets and their work:

Jacob Isaac Segal (1896-1954): A Montreal Yiddish Poet and His Milieu, Pierre Anctil

Dineh: An Autobiographical Novel, Ida Maze

Night Prayer and Other Poems, Melech ravitch

Paper Roses, Rachel Korn

Generations: Selected Poems, Rachel Korn

Exile At Last: Selected Poems, Chava Rosenfarb

Bociany, Chava Rosenfarb

Confessions of a Yiddish writer, and Other Essays, Chava Rosenfarb

Honey on the Page, Miriam Udel

Canadian Yiddish Writings, Abraham Boyarsky and Lazar Sarna

Writing in Tongues: Translating Yiddish in the Twentieth Century, Anita Norich

Dictionary of Literary Biography: Writer in Yiddish, V. 333, Joseph Sherman

Identity and Community: Reflections on English, Yiddish, and French Literature in Canada, Irving Massey

Jewish roots, Canadian soil : Yiddish culture in Montreal, 1905-1945, Rebecca Margolis

please visit us at the jpl for the PHYSICAL COMPANION EXHIBIT featured until AUGUST 1, 2023.

Meet our collaborators

JPL WISHES TO THANK DR. AARON KRISHTALKA AS WELL AS OUR 2023 RESIDENT SCHOLAR SARA CANTLER FOR THEIR INDISPENSABLE CONTRIBUTIONS TO CELEBRATING YIDDISH: I TURN TO THE POEMS OF MY FRIENDS.

SARA CANTLER

Sara has a background in History and is pursuing her masters at McGill University for Information Studies. She initially found her passion for libraries and archives during her time at Towson University in Maryland where she interned at the Cook Library Archives and Special Collections and had the opportunity to get a first-hand look at truly historic and invaluable materials, solidifying for her the importance of libraries and archives in the effort to maintain and preserve our collective history.

DR. AARON KRISHTALKA

Dr. Aaron Krishtalka was born in wartime Montreal and grew up in a literary, book and tradition-loving family—emigrants from southeastern Poland and Volynia, who spoke and sang, wrote, argued, and published in, taught, loved, and spread Yiddish. He launched into lifelong schooling in the Morris Winchevsky Shule in Montreal, and then entered stranger, broader lands at Baron Byng High School and McGill University. There, History drove him to an eventual PhD, and to teach European history at Dawson College and McGill University. Yiddish literature and letters, in books, journals, and latterly computer screens, kept him company all along, together with his bicycle and woodworking tools. He had the good fortune to marry Henie Shainblum (whose parents, among their many other talents, also spoke, sang, and taught in Yiddish), and together they have two sons, Gideon and Sholem.

!["Praise" handwritten Yiddish with Chava's English translation from "Prism International V. 5 #2", Autumn 1965, ID: JC_[YL]_Rosenfarb](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/646499d5-19dd-4f6c-8bfd-62c762751be8/JC_%5BYL%5D_Rosenfarb_Chava_3.jpg)

![Celebration of Life, "Ida Massey - The Person" written by Rita Brianksy and from "The Canadian Jewish Chronicle", June 14, 1963, ID: 1291_[18]_3](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/4935dec2-3fb6-4189-9211-2bd6e8228436/1291_%5B18%5D_3.png)

![Article "Writer Rosenfarb welcomed back to Montreal", from "The Canadian Jewish News", April, 2004, ID: JC_[YL]_Rosenfarb](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/1681128996600-8F76JOD8PIRI6L7C40LY/JC_%255BYL%255D_Rosenfarb_Chava_1.jpg)

![Article "Melech Ravitch, 70" from the "Congress Bulletin", December, 1963, ID: JC_[YL]_Ravitch](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/62b48292d1bcbc071b15094c/c9211651-6384-4293-8026-0d5c63a528f9/JC_%5BYL%5D_Ravitch_2.png)