antiquities of the jews

(Venice : Rinaldo de Novimagio, 1481)

-

Josephus’s background – from his 1st-century CE birth and maturity as a highly-educated, high-ranking Jew to his eventual defection and service to the Roman Empire – uniquely positioned him to write Antiquities of The Jews, commonly considered the first Jewish history that attempts to reconcile Biblical chronology with secular history. He aimed his work at a non-Jewish Roman and Greek audience whose prior experience of history amalgamated myths and political successions.

Modeled on a similar Roman history by the Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Antiquities tries to demonstrate that Jewish culture predates any other then-extant culture, an idea similar to that of Josephus’s predecessor Philo of Alexandria. Josephus likely wrote the work in Western Aramaic, though no extant manuscript remains, and completed its 20 volumes around 94 CE. The earliest manuscript copies are derived from Christian sources, including the earliest complete Greek version (11th-century CE). This has resulted in considerable scholarship dedicated to scrutinizing the work’s Testimonium Flavianum section discussing Jesus of Nazareth.

Antiquities’ first half essentially rephrases Biblical texts describing Jewish history from the creation until Persian rule. Josephus’ preface delineates his purpose in writing the text to dispel myths and misconceptions about the Jewish people – especially their perceived hostility and disloyalty, as well as the apparent lack of great historical figures among them. In this way, the book serves as an apologia, offering a Hellenized history of the Jews to the Roman rulers who had subjugated them.

This Hellenistic approach that Josephus employs to mollify the Roman elite results in interesting modifications to Jewish history. For example, Moses’ “Song of the Sea” at the Red Sea is omitted, but a song to God by Moses is composed in a distinctly Greek hexameter, and he additionally omits the story of the golden calf at Mount Sinai. He does, however, endeavour to elevate figures of biblical stories, making them ideal leaders in the eyes of the Romans: Abraham, he claims, taught science to the Egyptians who subsequently educated the Greeks.

To strengthen Antiquities’ reliability, he supports his version of the Biblical narrative with quotes from – for example – Berossus, who had read Babylonian sources, and Menander of Ephesus, who claimed to have studied Tyrian sources. Scholarly debate posits Alexander Polyhistor as Josephus’s intermediary and perhaps slightly unreliable source for these references.

The work of previous historians such as Nicolaus of Damascus and Polybius evidently informs Antiquities’ second portion, on the period between Alexander the Great and the First Jewish War of Josephus’s time (66-70 CE). In sections absent the now-lost original sources, Josephus likely rephrased the missing information.

Antiquities serves as both a Jewish and world history, and Josephus takes a Biblical perspective on God’s role in those two narratives’ intersecting events: As God used the Egyptians and other peoples to either punish or rescue the Jews, he now used the Romans to punish them. Josephus’s audience could easily understand this concept in terms of ‘Fortune’, ‘Destiny’ or ‘Fate’ rather than ‘God’. Still, even as Josephus uses one of these common pagan expressions, he must have had the Jewish God in mind –and so suggests Jews simply accept their history as God’s will.

The Testimonium Flavianum, one of Antiquities’ most remarkable passages, provides a near-contemporary account of Jesus of Nazareth. Considerable academic discussion revolves around whether Josephus’s narrative indicates he adopted Christianity, or – as Josephus never wrote any definitive statement to that effect – if that interpretation actually rests on subsequent Christian authors’ or copyists’ additions to the original manuscript.

Antiquities’ timeline includes the historical period – 175 BCE-66 CE – also covered in his previous work Jewish War (75 CE), a copy of which the JPL holds. Research indicates it never substantially revises War’s discussion of the era; usually, Josephus goes back to the same earlier historians and rephrases what he has read. As well, although Josephus does add materials, these originate from the Pharisees’ oral tradition.

Some editions of Antiquities also include Josephus’ autobiography.

Despite the misgivings one might hold against Josephus’s morality, actions or scholarship, Antiquities stands as a work of monumental importance. It comprises one of the only contemporaneous records of Judaism set against the backdrop of early Christianity, and so far remains the sole extant first-century, non-Christian account of Jesus of Nazareth’s life, teachings and death independent of the gospels. Lastly, its scope includes more than just historical accounts of events, but also descriptions of religious and institutional life, as well as the private lives of local citizenry.

-

Jerusalem-born Titus Flavius Josephus, né Yosef ben Matityahu (37 CE -100 CE) left behind a body of historical writings that, even today, make him a controversial figure. While they include a unique, valuable contemporaneous record of both the 1st-century Jewish rebellions against Roman rule in the Holy Land region known as Judea – as well as of Jesus of Nazareth – they also contain many autobiographical details that still remain as disputed and suspect as Josephus’s true loyalties. Regardless of one’s verdict about that, his works give readers a sense of the competing influences that his native Judaism and emerging Christianity had upon him.

Josephus and his brother had parents who represented the era’s transition between Jewish and non-Jewish control in Judea. His mother descended from the Hasmonean royal dynasty, the territory’s last Jewish rulers; his father, a high-ranking Kohen (Jewish priest), became known for his tactfulness towards the Roman Empire-backed Herodian dynasty that conquered Judea and supplanted the Hashmoneans in 37 BCE. Josephus later recounted his growing up in a privileged, wealthy lifestyle that included a full education.

At 16, Josephus apparently traveled on a 3-year long spiritual trek in the wilderness with a member of an ascetic Jewish sect. After his return to Jerusalem, he joined the Pharisees – another Jewish faction that, crucially, had no issue with non-Jewish rule of the Holy Land as long as they could practice their religion. On this point, as with many more to come, there exists much scholarly speculation as to whether Josephus actually believed in Pharisee dogma – or merely associated himself with the group as an opportunistic move in anticipation of what he may have considered an inevitable end: the defeat of Jewish revolt against Roman rule of Judea.

Despite overthrowing Judea’s Jewish kingdom 60 years earlier, the Roman regime still fought to consolidate their power against ongoing, if scattered, Jewish rebellions. The hostilities increased, and in his early twenties Josephus traveled to Rome to negotiate with Emperor Nero for the release and return of several captured Kohanim. While Josephus succeeded in his mission there, the Roman culture and sophistication he encountered apparently deeply impressed him – as did the Empire’s military might.

He returned to Jerusalem on the eve of the First Jewish War (66-70 CE), a general Jewish revolt across Judea led by the nationalist and militaristic Zealots who set up a revolutionary government. Josephus – a self-proclaimed moderate, at least in his memoirs –argued for conciliation with Roman forces. One could suggest that one or several factors motivated his stance: his alleged Pharisee beliefs, or his knowledge of Rome’s armed forces, or his elite background. However, in this instance the most logical explanation might again be simple expediency, which also might explain his subsequent actions.

When the Zealots achieved an early War victory in overrunning Jerusalem’s Roman garrison, Josephus pragmatically aligned himself with them. They appointed him their military commander in the Galilee region, although he still inclined towards conciliation with the Empire. His outlook conflicted with that of John of Giscala, a Galilean who had organized a private militia of peasants. Josephus and John wasted considerable time fighting for control of the rebel operations while the forces of Roman general – and future emperor – Vespasian prepared to attack. While Josephus later wrote that he assumed sole leadership of the Galilean rebels, his newfound status became a moot point.

In 67 CE, Vespasian’s army overwhelmingly destroyed most of the Galilean resistance within a few months. In his memoirs, Josephus recalled the Romans had him and around 40 fellow Jews under siege. Rather than surrender, the rebels chose to draw lots to determine the man who would kill the others and then commit suicide. Josephus claimed pure luck or divine intervention allowed him to ‘win’ this draw; whatever the true circumstances, he instead surrendered. Brought before Vespasian, he apparently avoided execution by yet another expedient action: predicting the former’s ascension as Emperor. This impressed Vespasian enough to spare the captured general’s life.

Josephus spent the next two years imprisoned in a Roman camp, while his forecast gained credibility after Nero’s death in 68 CE. The following year, Vespasian’s troops proclaimed him Emperor – and he gratefully freed Josephus. In turn, Josephus proclaimed allegiance to the Empire, adopting Vespasian’s family name Flavius as his own.

By 70 CE, Josephus joined the Roman forces under the command of Titus, Vespasian’s son and eventual successor as Emperor, as they began the War’s final battle: the siege of Jerusalem. Over 7 months of brutal fighting, Josephus attempted to act as a mediator between the Empire and the rebels, but his history of shifting alliances led both sides to mistrust him. When Jerusalem fell to the Empire, Josephus went to Rome where, granted full citizenship and a pension, he spent the rest of his life devoted to his literary pursuits. Besides a Spanish translation (1536) of his Jewish War, our collection includes a Latin translation of Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews from 1481, making it our earliest-dated item.

-

Rinaldo de Novimagio (active 1477-1496),most probably Netherlands-born, began printing in Venice in 1477 as partner to Theodor von Rynsburg, a German. In 1479 he established his own press, likely funded due to his marriage to Paula de Messina. De Messina had already outlived 2 successive husbands, both expatriate German Venetian printers: Johann of Speier – Venice’s first printer – and Johann of Cologne.

De Novimagio, using the 2 same Gothic typefaces as his former partner Rynsburg, released only 38 books during his 19 year career, mostly printed between 1477 and 1483. His wife’s death in 1480 may account for this sporadic output: De Novimagio and his 3 sons each inherited a considerable 500 ducats’ worth of gold and goods, and therefore he could afford to suspend his business with little financial worry.

Another explanation posits De Novimagio’s primary interest in creating typefaces — particularly a music typeface — rather than printing books. Contemporaneous and subsequent scholarly reviews of his press’s sole published music book suggest his efforts were regarded as incredibly flawed.

De Novimagio’s press ceased operations in 1496, although it is unknown if his death coincided with this instance. Other printers subsequently used his typefaces.

-

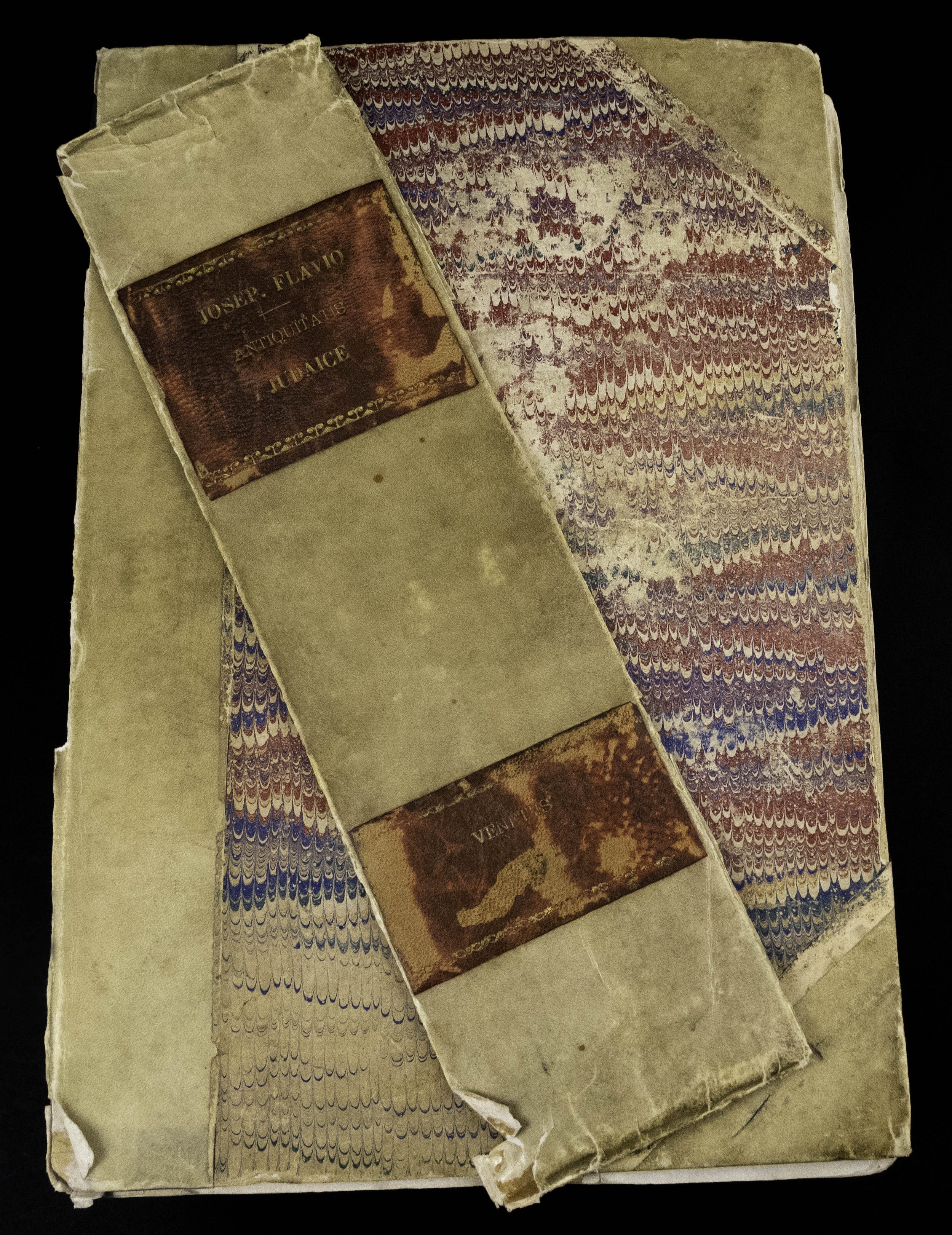

This is the JPL Rare Books collection’s earliest printed book, produced in Venice a mere 31 years after Johannes Gutenberg first successfully tested his revolutionary invention, the printing press. As one of our collection’s largest books as well – measuring at 30.5 x 21 x 8 cm and originally printed in two separate volumes – its size and weight definitely compel the reader to place it on a solid, sturdy table for perusal.

Its cover consists of red marbled paper with beige leather half binding, likely calfskin. A great deal of the paper’s colour has faded, while the center has considerable scuffing. The leather is in moderately good condition, though the corners are bumped. Unfortunately, while the bulk of the volume is perfectly intact, the binding has completely detached from it in three parts: the front cover, back cover, and spine. The spine has two red leather cases, one each at 11.4 cm from its top and bottom. Each also include gold decoration along the leather’s top and bottom edges. The top case indicates, in gold, “Josep. Flavio / Antiquitatis Judaice”, while the bottom case states “Venetiis” along with a date beneath it obscured by damage. The fore edge has “JOSEPHUS” written along it.

Upon opening the front cover, one sees a piece of paper taped into the water damaged pastedown. It displays a typewritten ownership statement: “FROM. M.C. Cole, Esq. Flat 16, 25 Cheyne Place, London, S.W.3.” The front flyleaf’s outer edge shows water damage as well as minimal tearing. About 2.5 cm from its top, repair work appears to have been done in a 9 x 2 cm section, perhaps where previous ownership had been indicated and subsequently removed. Newer than the following edge, it was possibly added when it was rebound with the marbled cover, which is not sympathetic to the original time of production, although it is possible the original calfskin binding was used for the half-binding.

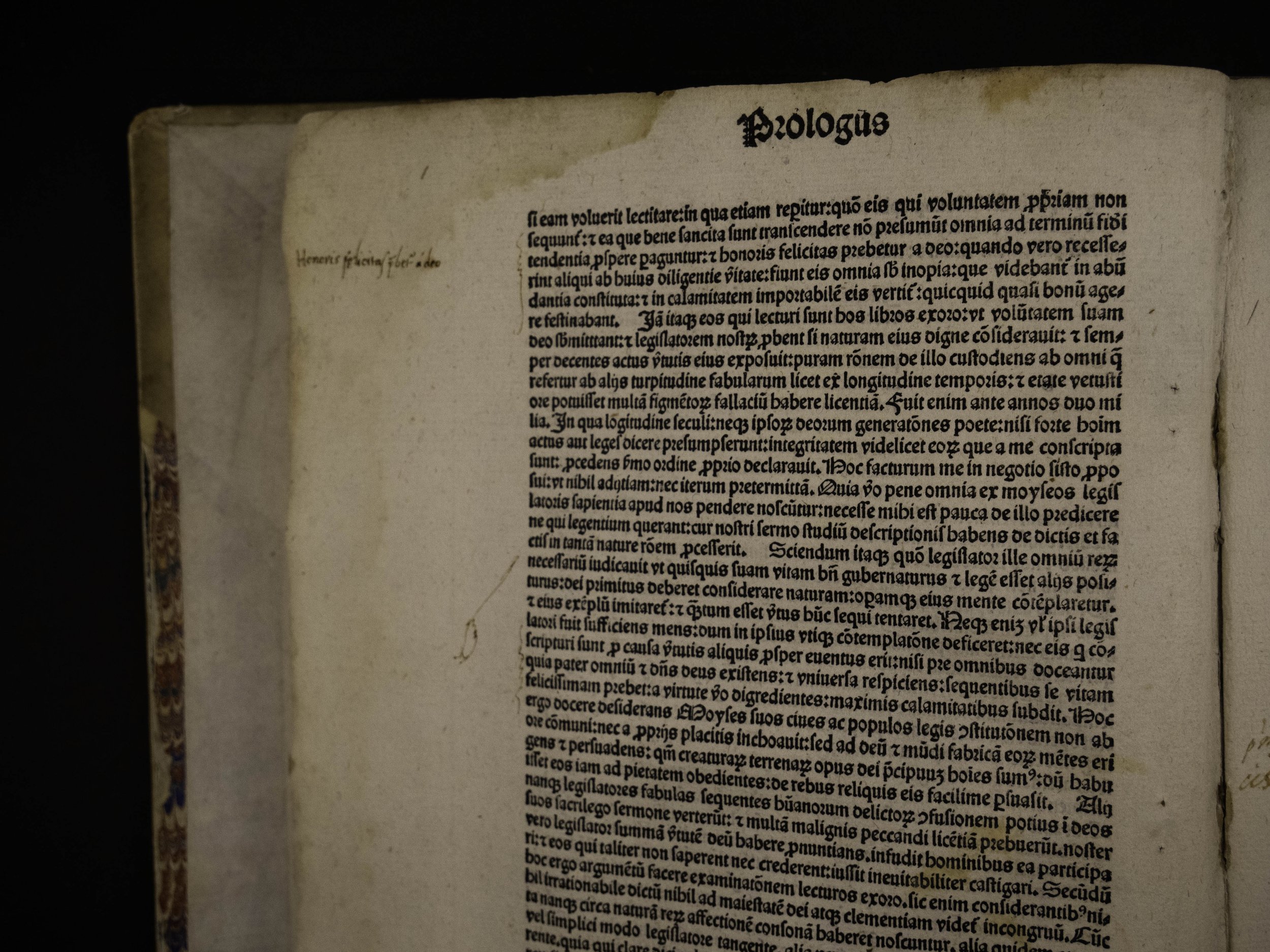

The original end page has a distinct upside-down crescent watermark with vertical chain lines, visible without aid at its center. This leaf is more damaged than its predecessor, though the water damage is identically placed. The work’s prologue begins on the next leaf, stating the work’s author and title. An illegible black ink stamp appears at both the bottom of the text and along the spine in the upper inner corner. The stamp seems to contain a crest, and there is transfer on the verso of the leaf preceding it.

The text proper begins with an empty case for an illuminated letter, in which a small letter ‘b’ has been printed in the center as a rubricator’s note. The type is elegantly cut in what appears to be Schwabacher blackletter, an early German form. The margins are very large by today’s standards, measuring 7.5 cm at the bottom, and 6 cm on the outer edge. The inner and upper margins, each a modest 2 cm, are more similar to today’s printing style.

Marginalia appears as early as the verso of the first printed leaf, and immediately two different hands are identifiable. On the verso of a2, a small hand in dark brown ink has made brief but legible notes in Latin, and added a manicula – a small illustration of a pointing hand – near the halfway point. In the inner margin of the recto of a3, a second writer, writing in much lighter brown ink has made nearly entirely illegible notes, also in Latin. This hand appears to have added a large “T” in an empty case on the verso of a3 in lieu of rubrication. Together, these two hands make notes throughout the prologue, though the smaller hand is more prolific.

What appears to be a third hand appears on the verso of a6 in a nearly black ink, less clear than the first hand but clearer than the second. The heavy marginalia continues through Liber Primus, but the second hand disappears nearly entirely halfway through it, making only very sporadic appearances afterwards. The first hand continues to make notes steadily throughout, including the charming manicula, and then appears to stop entirely at leaf i. Furthermore, the marginalia by the third hand stop with only very minor appearances afterwards at leaf q5, halfway through book 12. There is almost no marginalia between q5 and the end of book 20 in any of the identifiable hands.

Book 20 ends with a colophon in which De Novimagio takes responsibility for the printing of the work in May 1400 – though this is a printing error, as we know it to have been printed in 1481. The leaf’s verso is blank, and visible is a watermark unlike that at the work’s beginning: a circle which circumscribes two adjacent triangular shapes, with a star-topped staff above it. This is followed by an entirely blank leaf. Beyond this is appended Josephus’ The Jewish War, preceded by a prologue and in 7 books, from a2 to n5. Of interest, at least two of our three previously identified unknown writers’ inscriptions recur, as well as perhaps a fourth, who has taken pains to fill in most of the empty cases that should have been rubricated with the appropriate letter. At n5, the heading at the top that indicates the particular book of De Bello Judaico disappears, and it appears that Josephus’ Against Apion has been appended. The work ends on p5 with another colophon in which de Novimagio takes responsibility for the printing at Venice in March 1481. They have been bound in reverse order to preserve the chronology of events, rather than that of the writing.

The volume’s final two leaves are blank. A stamp identical to those on the first leaf has been placed at the bottom of the verso of p5 beneath the text. Unfortunately, its lack of legibility mirrors its counterparts. Some of its ink has transferred to the blank leaf, which is moderately more damaged than the front flyleaf. On its verso, “Momento di David [?]” is written in faded, elegant script ; the final word is illegible and appears to have been scrubbed out. The final flyleaf is minimally damaged, with some tearing along the top edge and the top corner folded, along with the corners of the three previous leaves. Located near the leaf’s center, there is a clearly-visible watermark of a circle in which a curved diamond has been drawn. Each of the circle’s five segments contains a six-pointed star, with the largest in the center segment. Of interest, p4 has visible the upside-down crescent watermark from the beginning of the work. The back pastedown is blank.