Derekh Emunah

(Padua : Lorenzo Pasquato or Samuel Boehm, 1563)

-

Spanish Kabbalist Meir ben Ezekiel Ibn Gabbai completed Derekh Emunah (“The Path of Faith”), his final work, in 1539. First printed in Constantinople (1560), Gabbai wrote this explanation of the kabbalistic doctrine of the Sefirot as a response to 10 questions posed by Joseph ha-Levi, one of his students. In a question and answer format, the book relies considerably upon 13th century kabbalist Azriel of Gerona’s Perush ‘Eser Sefirot, as well as the Zohar. Samuel Boehm – the renowned Hebrew printer, editor and typographer – briefly prefaces the work with an explanation of his role as its editor. He also wrote the equally perfunctory colophon that notes some errata. However, despite his seemingly modest statements, as well as printer Lorenzo Pasqualo’s title page credit, Boehm was likely Derekh’s actual printer. The book concludes with a censor’s statement authorizing this edition.

-

Little biographical information exists about Meir ben Ezekiel Ibn Gabbai (ca. 1480-1540). Likely Turkish-born, but associated with Spain, his works contributed significantly to Kabbalist theory, predating Moses Cordovero and Isaac Luria. Amongst his most popular, important writings, Avodat ha-Kodesh — his systematic framework for Kabbalah — reflects both his close study and fierce refutation of Maimonides. Derekh Emunah was Gabbai’s last work. He is thought to have died in Israel.

-

Since the 13th century, Jews had lived in Padua, near Venice and had established a yeshiva headed by the eminent rabbi Judah Minz. As well, the university there – Italy’s 2nd oldest, after Bologna –admitted and matriculated a relatively large number of Jewish students who constituted a significant cultural force in Padua and elsewhere. The city also had an early, distinguished history as a printing centre: from at least 1472 until 1600, nearly 30 printers operated there at one time or another.

Despite the fact that the Venetian rulers who came to govern Padua during that period established a Jewish ghetto in the early 1500s, on balance it may still appear somewhat surprising that Jewish book printing arrived relatively late to Padua in the form of Lorenzo Pasquale aka Lorenzo Pasquato (1523-1603). His press’s first book, Rabbi Meir Ezekiel Ibn Gabbai’s Derekh Emunah, appeared in 1562.

Pasquato, an experienced Christian publisher of Latin, Italian and Greek books, served as the University of Padua’s official printer, and as official typographer for two fairly obscure learned societies possibly affiliated with that institution: the Academy of the Courageous and the Academy of the Cursed. He likely branched out into Hebrew printing for the same reasons as did other Italian non-Jewish presses: with Catholic Church censorship efforts eventually leading to a 1553 ban on Hebrew printing in Venice, small presses elsewhere sought to replace the closed Venetian firms. As well, this niche market attracted less competition, and therefore greater chances for profitability, than the Italian-language book sector.

Pasquato hired Samuel Boehm as his firm’s main Hebrew printer, editor and corrector. Boehm – who had previously worked for Jewish presses in Venice and Cremona – seems the likely actual publisher of Derekh, using Pasquato’s facilities and imprint.

However, by 1563 Venice’s ban on Hebrew book printing had ended. Four years later, after publishing Rabbi Shem Tov ibn Shem Tov’s Derashot ha-Torah – again, probably Boehm’s production in all but name – Pasquato stopped printing Hebrew books, or any others, in Padua. His involvement in the Hebrew press’s operations seem minimal, at best; even his usual printer’s mark – a lion – makes no appearance on the title pages of Derekh and Derashot.

Pasquato relocated and shifted most of his business to Venice, where he remained an extremely prolific printer who published over 200 titles in total during his career. Pasquato’s two sons Livio and Giovanni Battista inherited his press; Giovanni served as a printer to the bishop.

Boehm apparently stayed in Padua and kept in touch with Pasquato until 1569, when he moved to Krakow to work for Isaac ben Aaron Prosnitz’s press. His departure ended the first, intermittent attempt to publish Hebrew books in Padua; other presses briefly opened during the 17th to 19th centuries.

-

Our copy of this short 28-leaf volume – the work’s 2nd printing (1563) – is one of but a handful of Hebrew books produced in Padua during the century after the 1553 Venetian ban on Hebrew printing. It measures 18.5 x 13.5 x 0.75 cm, rebound with cardboard covers wrapped in red, orange, and blue marbled paper with a cloth spine. Along the spine, a piece of paper roughly 1 cm wide with several visible typewritten English letters indicates the presence at one time of, perhaps, an identifying spine or cover label. As well, another faded spine portion 2.5 cm from the bottom suggests it once bore a starburst-shaped sticker.

Opening the book’s front cover reveals traces of other removed details. A sticker — perhaps an ex-libris plate — had been glued to and then removed from the front pastedown. Above it, two visible words (“title page”) of a mostly-erased, indecipherable 7-word long pencil inscription remain, with another word (“beautiful”) barely discernible.

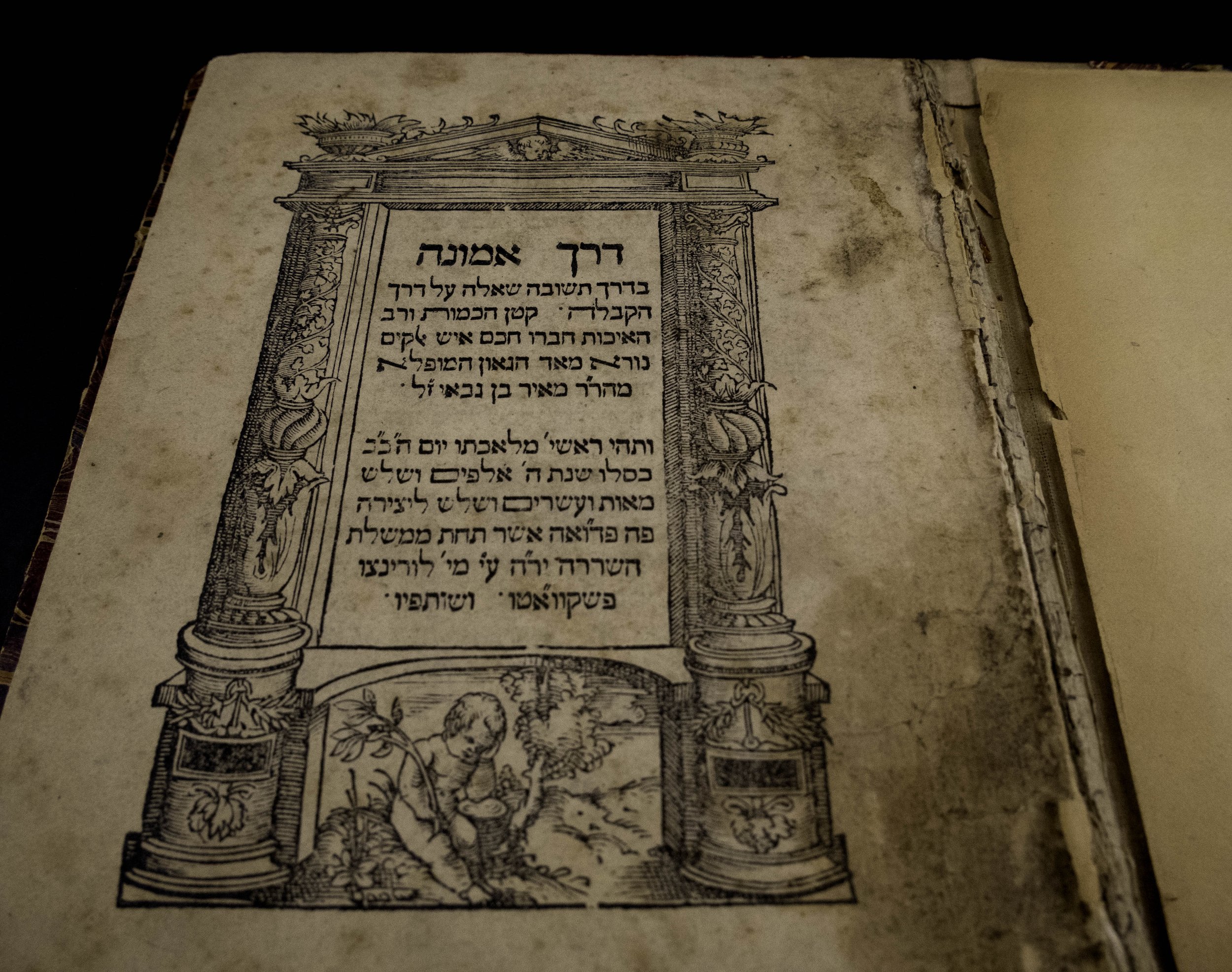

The title page has fairly severe foxing, but has suffered no other significant damage. It features a large woodcut architecture frame of an ornate gate that surrounds the book’s title and two text blocks. It sits 3.5 cm from the page bottom and 4 cm from the spine, leaving the already-wide margins quite uneven. Ivy vines wrap around the gate’s right and left pillars, each topped with torches. Beneath the gate arch’s peak, a cherub’s face and spread wings, drawn in minute detail, peek out.

A smaller, inset frame at bottom depicts a pensive child, sitting on an embankment and holding a branch with his right hand. He is resting his forehead in his left hand; a tree stump supports his left arm, bent at the elbow. Just beneath the arch, the book’s title appears in large Hebrew Ashkenazi block print, followed by a brief statement in smaller similar type indicating the book’s kabbalistic nature, as well as the date and place of printing and the name of the publisher, noted as “Lorenzo Pasquato and Partners”. The title page verso, written by the well-known typographer, editor and corrector Samuel Boehm, explains how he came to edit the work. Despite this rather modest statement, as well as the information on both the title page and the colophon soon to be described, Boehm was likely Derekh’s actual printer.

Gabbai’s short introduction begins the text proper, on the second leaf’s recto. That leaf immediately illustrates that Pasquato, or Boehm, justifiably earned a reputation for high-quality printing – but even the best-produced copies can subsequently suffer damage, as with our copy. Compared to Yale’s copy, which measures 21 cm high, our copy possibly underwent a poor rebinding effort that also probably included less than competent trimming. The evident results include a considerably wide margin along the spine – just shy of 3 cm – while the outer margin measures 0.5 cm. As well, the apparent offset printing vertically mimics this design, with even more egregious consequences. Furthermore, at the page’s top, one can see only the lower remnants of the first line’s cut-off text, even as the bottom margin measures a comfortable 2 cm beneath the signature and catchword. However, these issues do not consistently mar our copy. For example, on the top of the following leaf’s recto, the text has again vanished, but there is considerably more room along the outer margin; and on later leaves, the text has “slid” downwards on the page, rendering it entirely visible.

The text proper appears in single-column Hebrew Ashkenazi block print, with the exception of the final leaf’s very last portion. In the colophon there, Boehm writes that as the world is knowledgeable about the craft of printing, it is needless to apologize for the book’s few errors – which he then lists. He concludes by stating: “May blessings from heaven come upon the head of he who judges me favorably”. Immediately following this, the Latin, cursive typescript text states the Inquisitor’s license. A prerequisite to publishing Hebrew books in Italy, this license notes the permission to publish this book, along with the names of the Church officials who granted it.

The pages’ generally excellent condition shows only heavy discoloration, with no insect damage. They consist of relatively thin cloth paper with horizontal chain lines, with a watermark that appears to be a rudimentary anchor within a circle, topped by a staff with a star, with the star and staff appearing on the leaf preceding that with the anchor, along the spine in the centre. Only the 4th leaf requires any repair, as it contains a poorly-constructed patch 2/3rds down the outer edge, partially obscuring the text on the recto. Unlike the front-end page, the final end-page is loose but present and the pastedown is blank. Despite the intact spine binding retaining all the book’s pages, the pages themselves have detached completely from the new, cardboard binding. That binding is wholly intact, with no breakage along the spine.