Sefer brant shpigl

(Frankfurt am Main : No publisher listed, 1676)

-

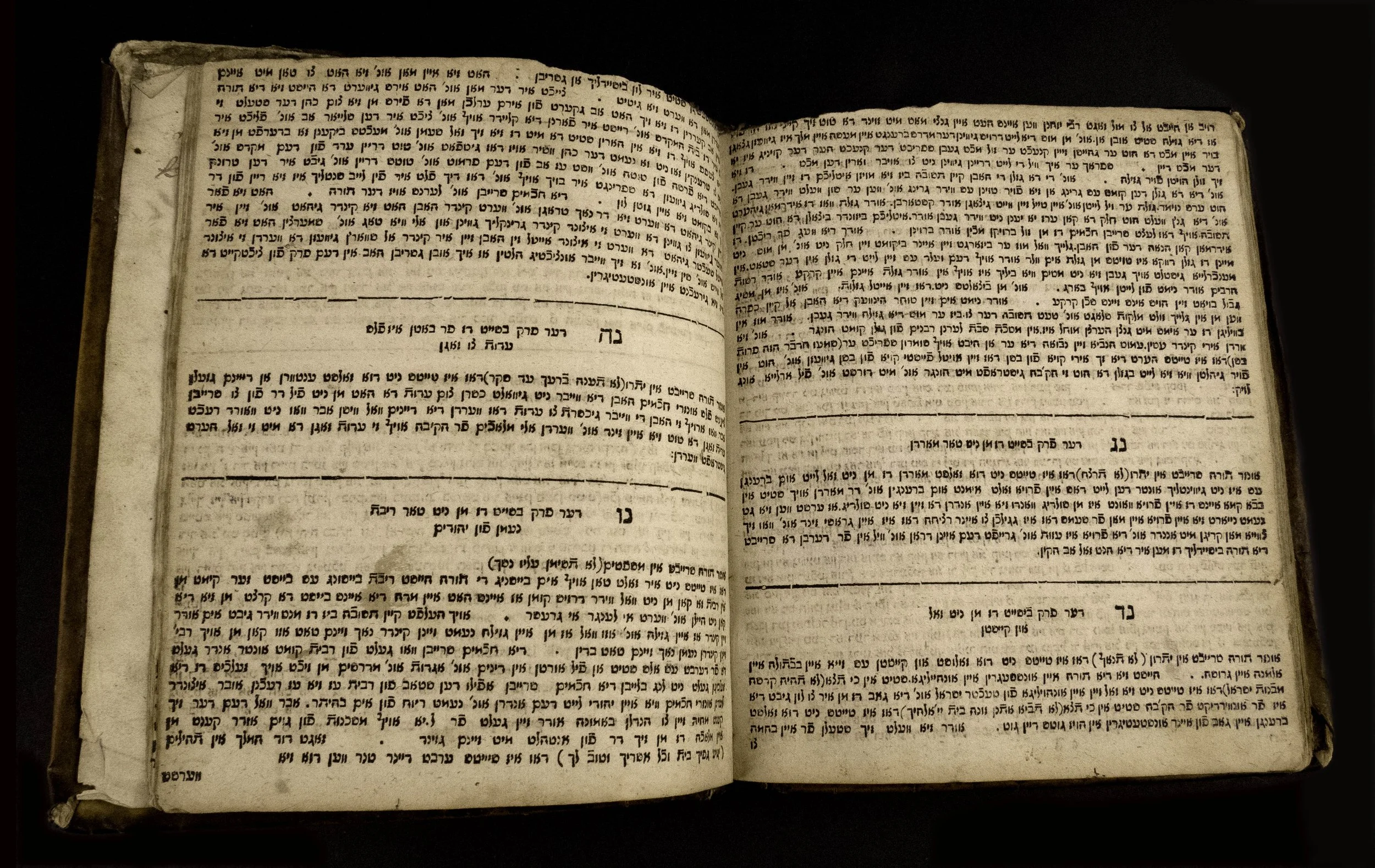

Printed for the first time in Krakow (1596), Brant Shpigl (“The Burning Mirror”) not only belongs to the genre of musar literature intended to teach morality and ethics, it also stands as that category’s first work originally written in Yiddish (technically, Taytsh-Deutsch, (adapted-German). Author Moses Altshuler wrote Brant specifically for Jewish women as a guide for being good wives and modest females. In this way, it is again the first of its kind: at this time, most works on musar were written for both men and women, or only for men.

In Brant, Altshuler explicitly explains his choice to write in Yiddish. He remarks that women do not know Hebrew and are forbidden to pray and study in that holy language reserved for men only. Therefore, women are ignorant of Torah and halakha (Jewish law), as are “men who are like women”, i.e. uneducated men. Using Hebrew to write a book aimed at women would have rendered it inaccessible to most of them.

The book contains mostly predictable content. It strongly emphasizes subjects like menstruation and cleanliness, for which Altshuler incorporates an extreme, excessive analogy comparing menstrual impurity to a serpent’s venom. Sexuality barely rates a mention, unlike in similar didactic works meant for males: Altshuler, it seems, could not conceive of women as inherently sexual beings. Instead, he simply reiterates ideals of feminine purity and modesty. He also affirms that a woman could best earn her place in Paradise by practicing exemplary domesticity: caring for her husband’s physical needs – including a hot meal and clean home – and tending to her children’s spiritual needs. Altshuler underscores that latter role’s significance and importance, asserting women’s crucial part in ensuring their children study Torah and become good, moral Jews. Besides these concerns, he also attempts to edify his female readers with recommendations for the appropriate treatment of servants, as well as for a married woman’s role in helping an unmarried peer attract a husband.

Immediately and immensely popular, Brant was reprinted 3 times during Altshuler’s lifetime, along with reprints in 1676 and 1706. The JPL holds one copy each of those latter versions.

-

Few biographical details exist regarding Talmudist and early Yiddish writer Moses ben Henochs Altshuler (c. 1546-1633).Nevertheless, his authoring of Brant Shpigl provides an appropriately mirror-like look into traditional Jewish social attitudes towards women at the time; and his work influenced countless imitations.

-

Brant Shpigl exemplifies the role women played in Yiddish printing’s history.

From the 1540s onward Eastern Europe’s Jewish printers flourished, but it took them several decades to appreciate and appeal to an inordinately literate Ashkenazi Jewish market hungry for edifying, moralistic literature in a language accessible to them: Jewish women, who primarily comprised that audience. In a time when Christian women were rarely educated, and even fewer involved in literary matters, Jewish women began playing a central role in Yiddish printing, working as typesetters, proofreaders, printers and authors. Copies of early, surviving books in this era, such as Brant, clearly speak to their importance: their title pages allude they were these works’ intended audience, and books intended specifically for them – or women and men – make up the bulk of the titles offered. As for Yiddish books solely aimed at men? A rarity.

Several reasons account for this unique situation. On one hand, only men had access to Hebrew – the language of worship and study – and so didactic books written in the vernacular were more likely to find a female audience. On the other hand, of course, those books had to be produced in Yiddish to reach that audience. The traditional Jewish view of women deemed it necessary that wives and mothers, being critical to their children’s religious upbringing and learning, needed education sufficient to shoulder this spiritual responsibility. Although literate, Jewish women were still considered uneducated compared to their male counterparts, but Yiddish printing provided — for the first time — a codified means to give them a way in which to solidify their own spiritual and religious life, as prayers and songs specifically for women became one of Yiddish literature’s most popular genres. Hebrew, and Hebrew printing, had long left a gap that Yiddish and Yiddish printing then filled.

At first, Yiddish printers did not limit their ‘women’s books’ to spiritual and religious topics. They also translated popular Christian epic romances and legends like Bevis of Hampton, King Arthur, Dietrich von Bern, and the Hildebrandslied. However, rabbis and religious book authors quickly discouraged them; instead, the printers began offering translated Biblical epics regarded as more suitable reading material for women: the Book of Samuel, the Book of Esther, and a version of the Book of Kings that re-situated the story as a courtly romance.

Although women greatly valued these Yiddish books, the actual production methods used for these works frequently reflected a somewhat devalued status for them within the larger Jewish society. No matter one’s viewpoint about contemporaneous Judaism’s attitudes towards women, the historical record certainly suggests that works generally written for them, in a vernacular language, merited no intrinsic appreciation other than their basic educational and social utility. Even religious texts, once translated into and printed in Yiddish, were no longer considered holy. Consequently, Hebrew books were often beautifully crafted while Yiddish ones were printed as cheaply as possible with very narrow margins, thin paper, simple leather bindings and so on. As a result, fewer of them survived than their Hebrew equivalents.

-

The JPL holds 2 copies of Brant, both printed in Frankfurt am Main. One, from 1676, is quite spectacular. It measures 20.5 x 16.5 x 2.5 cm. Still in its original light brown leather binding, one can easily discover the contrast of its shoddy construction, compared to contemporaneous standards, with the formidable value it held for its owners.

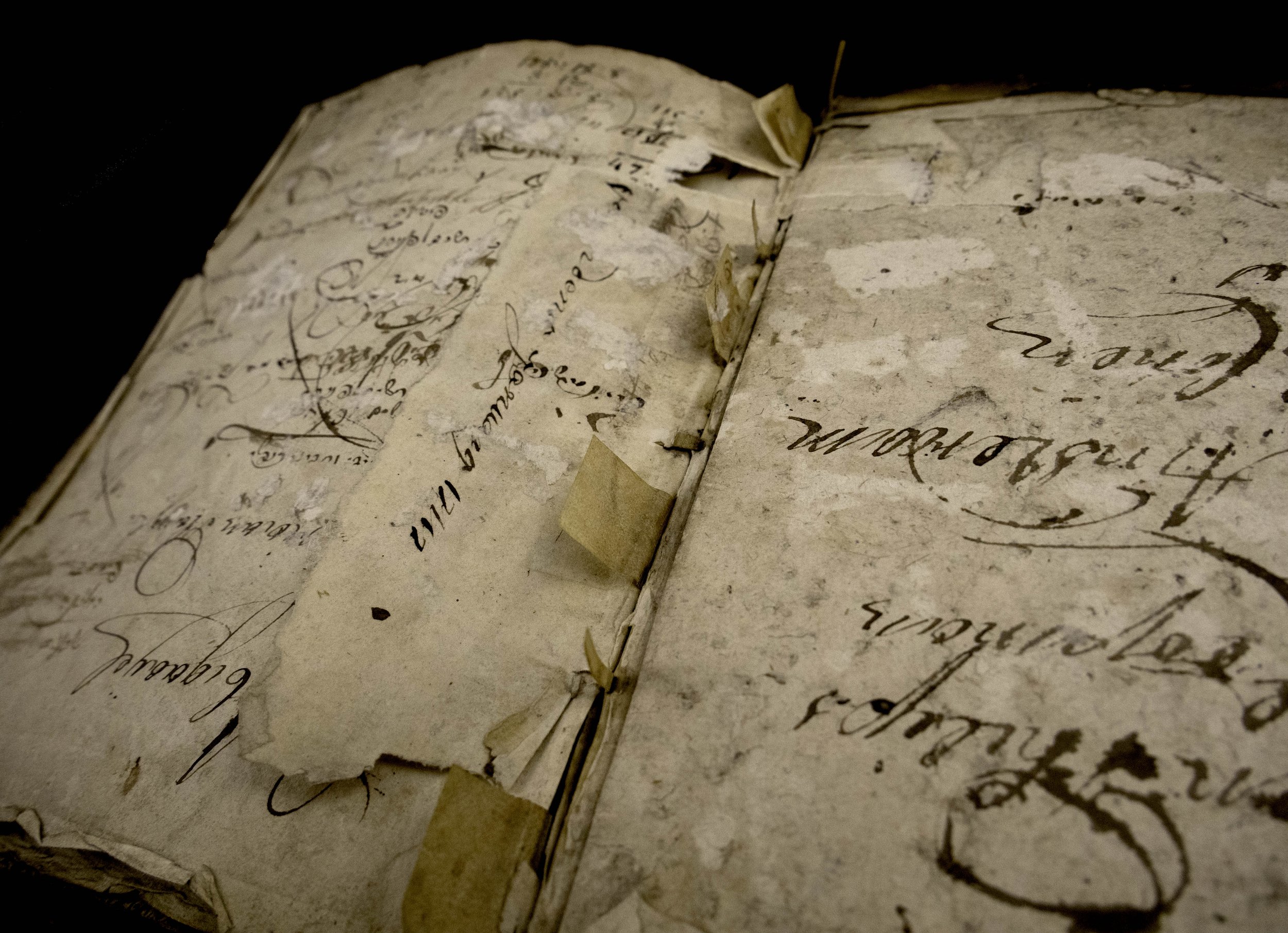

The leather is cut and secured unevenly to the board beneath it, and the string binding the spine is visible through the leather’s joints. The front cover shows significant discoloration, and someone once inscribed the book’s title in ink, but it has faded so that only the Hebrew word sefer (“book”) remains visible.

Opening the book reveals evidence of its frequent usage at the hands of numerous owners. 2 leaves, and a partial 3rd leaf, precede the title page. Pencilled handwriting covers those leaves’ rectos and versos, along with the end page. The inscriptions – varying in size, weight, language, page orientation and legibility – include one transferred from a now-absent page onto the end page. Some, in mostly faded, crabbed Yiddish, appear to be as old as the book itself; others are written in dark ink and a large, looping hand. Many run into and over each other.

The 2 initial leaves’ verso inscriptions are the easiest to read. On the 1st leaf verso, one owner declares (in Dutch) her love for the book, to the extent of branding any unauthorized viewer or reader as a thief and instructing that person – in quite graphic, crude detail – to sit on a barrel and experience the empirical evidence gleaned from having insects invade one’s interior space – a posteriori – as it were.

The 2nd leaf recto contains less writing than the preceding page. Someone carefully inscribed, in Hebrew block print, the work’s title. Beneath that, in similarly handwritten block Yiddish print, there appears “To Marana (i.e. Aramaic for “Our master” or “Our teacher”) Moses, the son of Henokh, a man of Jerusalem zetsl”; that final Hebrew acronym indicates the named person is ‘of blessed memory’ –that is, deceased. On the verso, the previously mentioned extremely protective owner wrote (in Dutch) “This book belongs to Mr. L.F. Gazan”, indicating a known Dutch Jewish surname. Underneath this statement, a series of letters appears; curiously, Mr. Gazan re-wrote his name immediately below these letters, but in reverse order. The word “Amsterdam” is visible behind this writing in a much older, brown-inked script. Other words and names are far more difficult to discern. The handwritten, upside-down text on the end page includes the words “Amsterdam”, “Samuel Cohen” (possibly) and “Lion Cohen Philips”. That last name, however, possibly indicates Philips – the Jewish founder of the multinational electronics conglomerate still in business – once owned this copy.

Handwriting also covers the end pages at the back of the book. While the last two pages are stuck together, unfortunately, the handwriting on the last page’s recto seems to match that on the front end page. Regrettably, heavy ink spots cover significant parts of it, making it mostly impossible to decipher. One can figure out some place names, like Rotterdam, as can the Dutch original of “Sir Levy Simon”.

The 2nd page’s verso bears a strange statement, handwritten in Dutch: “mijn man en deijn man mijn [?] en deign [?] en onse beijde kindert [?] enhel it log maaneen.” Beneath it, one pencilled handwritten Yiddish line appears.

An ornate frame wraps around the entire outer edge of the book’s title page. Poorly laid out, and set crookedly, parts of the frame are cut off on the page’s bottom edge and along the lower corner of its outer edge. The title is printed in neat block type, with Rashi script text beneath. An interesting image occupies almost the entire lower half of the frame’s internal space: a shield of sorts, with a lion’s face at centre, that appears to be simply an ornament and not a printer’s mark as expected. The text proper begins immediately on the title page verso; the type is set so there are no margins to speak of. In fact, some of the text slides right off the page. The paper itself remains in good condition: although the first couple of leaves show considerable wear along the edges, no other notable damage exists except for some discoloration.

Our second copy, from 1706, was rebound as evidenced by the addition of an end page at both the front and back covers. Sections of text are visibly cut off at the top and bottom of numerous pages, and several other pages have been repaired with tape.