Netivot ‘olam

(London : A. McIntosh, 1839)

-

English theologian and missionary Alexander McCaul’s Old Paths first appeared as a series of pamphlets published weekly between 1836 and 1837.Each addressed a different principle or practice of what was then considered contemporary Judaism based on the Talmud and rabbinical literature, contrasting it with Mosaic Judaism – the Old Testament’s laws, customs and practices.

In 1837, the complete series was gathered into one volume. In its introduction, McCaul – a Hebraist, devout Christian, and Protestant cleric -clearly states his goal of converting Jews to Christianity. To that end, he notes his intention to forgo the approach shared by many of his fellow Hebraists who often took an accusatory tone towards Jews. He also espouses respect for Judaism and Jews, referring to his profound knowledge of rabbinical literature. However, that respect did not embrace their right to practice their religion unmolested: in Old Paths, McCaul deploys his vast knowledge of Jewish religious thought and practice in order to undermine it.

He writes that contemporary Judaism’s practices are erroneous, basing his critique on the words of Moses and the Prophets. While McCaul then expresses difficulty in knowing Judaism’s true character, he still posits and explains his theory of it. He subsequently advocates the removal of Judaism’s “most pernicious elements” – Talmudic and rabbinic-based tenets and practices – as necessary for a Jewish return to Mosaic Judaism that will ultimately lead them to the “true” Mosaic faith: evangelical Christianity.

Old Paths’ 2nd edition (1846) added McCaul’s reflections about the original edition’s subsequent translations into German, French and Hebrew – the JPL holds the latter version – and its evidently favourable reception. He remarks that new synagogues emerged, renouncing the practices pronounced objectionable in that edition. By contrast, he accuses Jews still adhering to Talmudic and Rabbinic Judaism of wrongly categorizing his book as traditional antisemitism and anti-Jewish prejudice. Calling such Jews “victims of tradition” dictated by Talmudic era rabbis and perpetuated by contemporaneous ones, McCaul celebrates the Talmud’s translation into European languages as the precursor for that tradition’s inevitable downfall.

Old Paths does, indeed, attack Talmudism and the Talmud generally. The initial title portion of an 1880 reprint – The Talmud Tested by Scripture… – explicitly alludes to McCaul’s ‘testing’ the Talmud, and finding it ‘failing’ versus Mosaic Judaism: an assertion certain opponents might find anti-Jewish. Even those Jews concurring with him may have still regarded Old Paths as anti-Jewish, given McCaul’s overt aim. However, the Jewish community did not entirely repudiate his book.

-

In 1821, the 16-year old London Society for Promoting Christianity Among The Jews sent a well-educated, Protestant missionary to Poland: Dublin-born Alexander McCaul (1799-1863). For the next decade or so, his ever-growing professional accomplishments in Warsaw, Saint Petersburg and Berlin had him meeting figures like Russia’s Tsar Alexander I and Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich, as well as Prussia’s crown prince Friedrich Wilhelm IV. While on the Continent, McCaul also learned Hebrew and German. Knowing these languages surely aided him in studying Biblical, Talmudic and rabbinical texts, which in turn may have partly inspired some of his concern and affection towards those Jews whom he encountered in his missionary work – even as he still also demonstrated traditional prejudices against them.

Due to health concerns, McCaul returned to London in 1832. There, his active support of the Society included his helping found its Operative Jewish Converts’ Institution, a printing press and bookbinding trade school.

In 1837, he started publishing Old Paths – a recurring pamphlet on Jewish ritual that ran for 60 weeks. Within a few years, that led to his 2nd major career as a Hebraist. In 1840, he was appointed principal of the Society’s Hebrew college. The following summer, with the Anglican Church and Prussian Evangelical Church’s joint intention to establish a foothold in Palestine, Friedrich Wilhelm IV – McCaul’s acquaintance, and now Prussia’s Kaiser – offered him the position of their bishop in Jerusalem. However, McCaul thought a convert from Judaism would be more suitable and so successfully nominated his friend Michael Solomon Alexander, a convert and former rabbi turned professor of Hebrew and rabbinical literature at London’s King’s College. McCaul took on Alexander’s professorship there, and was also subsequently elected its first chair of divinity in 1846.

In 1843 McCaul was appointed rector at St. James Duke’s Place, an Anglican church whose location in a London parish with increasing numbers of Jewish residents eventually contributed to its demise. Perhaps as a consolation, he was appointed to an administrative post at St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1845 but declined requests to serve as a bishop in Australia and South Africa, electing instead to become proctor of St. Magnus-the-Martyr parish in 1850. 2 years later, McCaul was elected proctor for London’s clergy and held this position until his death.

Besides Old Paths, McCaul’s major works include A Hebrew Primer (1844) and lectures he gave as part of the annual Warburton series held in London to spotlight theologians and clerics (1846, 1852). However, his most enduring legacy was his daughter, Elizabeth Anne. A writer and social activist, she founded a charity in 1897 providing financial relief and employment assistance to those whose incomes fell below the poverty line due to old age, illness, social isolation, or disability.

-

Kazimierz Dolny (Poland)-born Stanislaus (né Yehezkel) Hoga (1791-1860) was the son of a Hasidic rabbi and adherent of Rabbi Jacob Isaac Horowitz, the “Seer of Lublin”. He received a traditional rabbinic education, acquiring a reputation as an academic wunderkind. At 13, he married the daughter of his hometown’s wealthiest merchant; as his dowry, Hoga and his 12-year old bride lived in his father-in-law’s home. There, a Danzig merchant impressed with Hoga’s scholarly achievements persuaded his father-in-law to let him learn modern languages, and provided him books for studying them. Nevertheless, Hoga remained confined by Hasidic society. However, his exploits still attracted the local Polish intelligentsia’s interest – as well as that of an influential noble in nearby Pulawy, who took the extraordinary step of traveling to meet Hoga in person.

British-educated Prince Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski’s family had owned Pulawy’s estates for almost a century before he inherited control in 1784. The prince had chosen to become a patron of the arts rather than accept his birthright to take over the Polish crown, already under threat from the Russian and Prussian attempts to partition and rule the country that would ultimately succeed in 1795. He made his permanent palace residence in Pulawy, and along with his wife Princess Izabela transformed the city into a major cultural and political center known as the “Polish Athens”. Notably, the prince regarded his Jewish subjects as deserving of equal rights and emancipation.

During the prince’s visit, Hoga modestly stated he knew nothing of Czartoryski’s learning. He then quickly accepted the flattered prince’s offer to study in his palace’s well-stocked library, while boarding with local Jews and retaining his Jewish clothing. At the library, Hoga began learning several foreign languages and also socialized and debated with educated Poles. In this atmosphere, he apparently began distancing himself from his native Judaism.

Hoga’s linguistic knowledge first proved useful during the War of the 4th Coalition pitting Prussia, Russia, Saxony, Sweden and Great Britain against Bonaparte’s France. Between 1807 and 1809, as Napoleon’s army invaded Prussian-controlled Polish territories, Jews there suffered considerable hardship due to language barriers. Kazimierz Dolny’s Jews, luckily, had Hoga to serve as their interpreter and mediator with the French and Poles.

In May 1808, the Polish general responsible for those disputed regions issued a military conscription order that included a Jewish quota. Hoga, using his connection with Czartoryski, obtained an exemption for his hometown – with the sole proviso of permission to openly mock his native Hasidic community. So granted, Hoga subsequently adopted European dress and cut off his earlocks. This earned him the community’s enmity and the moniker Meshumad – apostate – long before conversion had likely even entered his thoughts.

In the aftermath of Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, Hoga visited Adam Jerzy Czartoryski – Adam Kazimierz’s son – in Pulawy. 20 years earlier, with Poland no longer an independent nation but partitioned into foreign-held territories, the Russian tsar had ordered Czartoryski and his brother to serve in the Russian military. This led to them regaining part of their confiscated estates and, eventually, to Adam Jerzy’s appointment as a foreign minister by his close friend, Tsar Alexander I. In that capacity, Adam Jerzy went to the Congress of Vienna in May 1815, accompanied by Hoga.

The Congress’s agenda in establishing a lasting peace throughout Europe included the drawing up of a new Constitution of Poland. Expectations emerged that the Tsar would nominate Adam Jerzy as his deputy in Poland. Therefore, Kazimierz Dolny’s Jewry began rethinking their animosity to Hoga, in hope that his association with Adam Jerzy would lead to the Congress to respond positively to their concerns. Unfortunately, the Tsar appointed someone else, and Hoga consequently returned home with his reputation more diminished than before.

Kazimierz Dolny’s Jews again began scorning Hoga’s irreligiousness. Furthermore, his early marriage had resulted in three sons – and much unhappiness between him and his wife. Hoga soon vanished, and rumormongers noted that Yitta, a young woman often seen accompanying him on walks through town, had also disappeared. The two ended up in Warsaw in 1817.

There, Hoga called on Adam Chalmelewski, a university Hebrew and Rabbinic professor also appointed as the Polish government’s chief censor. Chalmelewski, needing an assistant to censor Jewish works, publicly appointed Hoga along with two anti-Hasidic Jewish scholars, and obtained permission for him to live in areas normally off-limits to Jews. Over the next 2 years, Warsaw’s Jewish community grew more aware of Hoga’s work. One of its leading members approached him to determine his influence, if any, upon the Polish government’s concurrent debates on the Jews’ legal status. As a result, he became the community’s unofficial political advisor, and again caught the attention of a leading figure.

By 1819, the government had appointed Luigi Chiarini, an Italian abbé and Warsaw University professor of history and Oriental languages, as president of the censoring “Commission for Jewish Writings and Publications”. Its wide-ranging mandate also included organizing schools for Jewish children and establishing Hebrew courses to enable Christians to study Jewish history and rabbinical literature. These two endeavors, of course, also allowed opportunities to advance the probable “Polonisation” or assimilation of Polish Jews, as well as their potential conversion to Christianity.

Chiarini’s primary Committee responsibility involved translating the Babylonian Talmud. Only 2 of 6 planned volumes ever appeared, amid much criticism for their containing many faults. Ironically, in a lengthy volume serving as that translation’s preface, Chiarini expressed many of the conflicting complimentary and derogatory ideas about Jews and Judaism later echoed by an English theologian and missionary soon to play a significant role in Hoga’s life: Alexander McCaul.

Hoga became Chiarini’s deputy, and no doubt felt ever-growing pressure and influence to repudiate his Jewish faith formally, although his life and career still certainly suggested his conflicted nature. For instance, he published two works in Polish in 1822: a translation of Hebrew prayers, and a treatise on Jewish laws and ceremonies. Yet in 1824, during a Polish state investigation of Hasidism, he defended it during the preparation of a report for the Committee of Religious Affairs, and during a public disputation. One would question what finally caused Hoga to convert; events in his private life proved the turning point.

Word of Hoga’s successful defense of Hasidism reached his hometown, and his father went to Warsaw hoping to effect a reconciliation between Hoga and his abandoned wife. Hoga, now living in a non-Jewish part of Warsaw with Yitta and their two daughters, met his father at the home of the Jewish community leader who had approached him years before. The encounter exposed Hoga’s Hasidic roots publicly, and when Hoga refused to return to Kazimierz Dolny with his father, the community leader’s wife – a Hasid herself – vehemently objected. She subsequently hired men to spy on Hoga, and discovered Yitta’s existence. She then threatened Hoga that unless he returned to his wife, she would inform his employers about his relationship with Yitta.

Hoga had falsely registered his illegitimate children with the authorities, and feared possibly losing his job and the prospect of imprisonment. He confessed to Chiarini, who suggested the entire family’s immediate Christian baptism as the sole means of evading such consequences. Hoga acquiesced, and in 1825 assumed the given name Stanislaus.

The conversion shocked the Polish government, which felt Hoga’s new status as a convert would compromise their Polonisation efforts, and that his fellow Jews would likely spurn his writings. As a result, it removed Hoga’s books from circulation, and later reissued them without crediting him. It also removed him from the censorship Commission. Warsaw Jewry also suspected Hoga would now turn against his former compatriots; however, the historical record indicates their fears were unfounded.

Despite his career setbacks, Hoga’s fortunes soon improved again. The same year as Hoga’s conversion, Tsar Alexander I set up a Jewish commission composed of non-Jews for the improvement of Polish Jewry’s condition; he appointed Hoga its secretary. The tsar also created an advisory committee on the matter, staffed solely by Warsaw Jews, which soon found itself bombarded by letters from Jews across Poland. Hoga ended up translating most of this correspondence into Polish for the committee’s benefit. That work, along with his suggestion – unheeded – that the non-Jewish commissioners contact Jews countrywide for input, restored his prestige with Jews across the political and religious spectra.

However, the Russian government noted the Commission’s tendency to propose privileges for Jews that far exceeded those existing in Saint Petersburg, the government’s seat of power. It ordered the commission’s dissolution as soon as possible; in anticipation of the process, it appointed Hoga’s mentor Chiarini as his replacement with the justification that “even converted Jews are not to be trusted”.

Chiarini, at this time, had also published a Polish article purporting to be an exposure of the Talmud, and proposed establishing a Jewish press under government control that would only publish approved Jewish religious books based solely on Scripture. The government would then seize the Talmud and all other rabbinical literature.

Polish Jewry again sought Hoga’s help, and he influenced his two former colleagues on the commission’s Jewish advisory committee to publish brochures denigrating Chiarini’s knowledge of Jewish religious literature. Chiarini retaliated by publishing a 2-volume book, in French, on his theory of Judaism and reform of Jews. For several years afterwards, this work fueled claims of Jewish blood libel, but Hoga and his colleagues’ letters to the press helped to dispel these accusations. However, Chiarini persisted, intending to publish a Polish abridged version of his book in 1830. The Jewish advisory committee, seeing it would directly incite reprisals against Polish Jews, successfully petitioned the censorship Commission to ban its publication.

In 1832, Chiarini died. The Warsaw municipality acquired his library, at Russian Tsar Nicholas I’s request, and it contracted Hoga to use the facility and translate the Talmud into Polish on the same terms as had been agreed with Chiarini during the latter’s employment with the censorship Commission. Remarkably, but perhaps unsurprisingly, Hoga vanished once again.

Rumors spread that Hoga and family had left Poland to return to their Jewish faith. While no definitive record accounts for Yitta or the children’s subsequent whereabouts, it is however certain that Hoga settled in London. He probably emigrated there due to the influence of none other than Alexander McCaul, who had met him while stationed in Warsaw as a missionary for the London Society for Promoting Christianity Among the Jews.

In London, Hoga translated the New Testament (1838) into Hebrew. He subsequently translated McCaul’s Old Paths into Hebrew as Netivot ‘Olam (1839), one copy of which is included in the JPL’s Rare books collection. While other translations of McCaul’s book into German, French, Italian and Yiddish would also inflame controversy and conversation during much of the last half of the 19th century, Netivot caused the most panic among Jewish community leaders throughout Europe and the Middle East. To them, Hoga’s contribution to a book printed in the Holy Tongue — which used the Old Testament and Bible to attack the rabbinate and encourage anti-Talmudism — betrayed his former community incredibly, and might deeply undermine its morale.

Hoga also produced Songs of Zion, an idiosyncratic Hebrew translation of English and German church hymns (1834) that arguably reflects his first stirrings of regret at his conversion; a Hebrew translation of Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1844); and various original English-language proselytizing books. By the mid-1840s, Hoga’s repentant frame of mind had led him to increasingly overt criticism of the London Society. For example, in Controversy of Zion: a Meditation on Judaism and Christianity (1845), he took the stance that his fellow Jewish converts to Christianity should still follow traditional Jewish law. Two years later, he wrote an article in London’s Jewish Chronicle that bitterly attacked McCaul and refuted Old Paths, and followed that up with The Faithful Missionary (1847), a pamphlet exposé of the Society’s operations. By 1849, Hoga had fully broken with the Society; in his last years before his death in London, he devoted himself solely to scientific interests, including patenting several electrical devices.

-

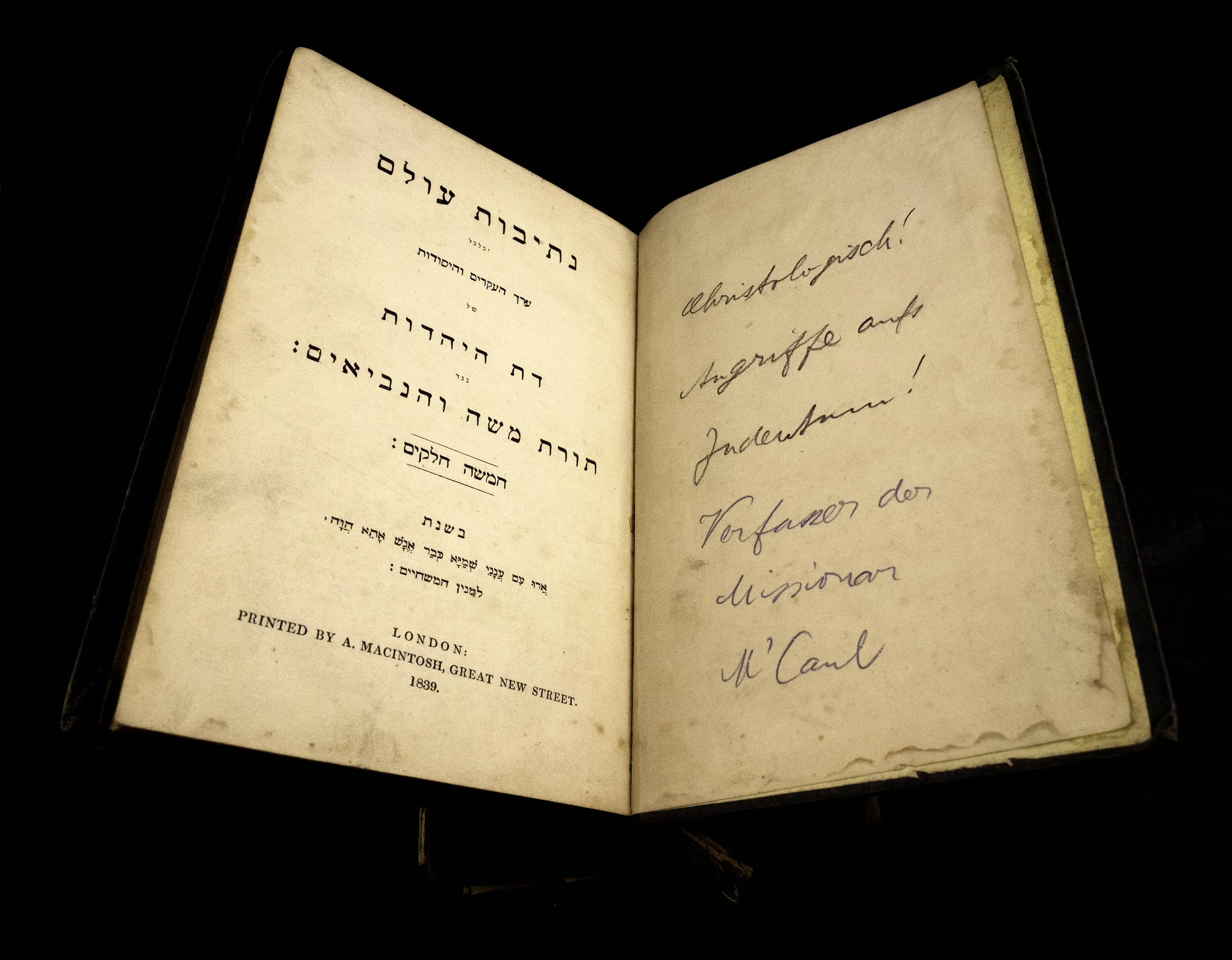

All 3 JPL copies of Netivot ‘Olam, the Hebrew literal translation of the original’s title, were printed in London in 1839. All are identical, including their original bindings, but we have chosen to describe the 1 copy with extraneous detail. Other than the expected differences in their patterns of wear, this copy’s physical details apply to the other 2. It measures 22.5 x 14 x approximately 2 cm. Its black fabric binding displays a pattern of vines and flowers on both the front and back covers. Along the spine, gilded Hebrew characters spell out the book’s title. The book’s corners are bent, with a bit of fraying along the outside edges. The front cover has sustained more wear than the black, with apparent water damage.

Upon opening the book, we encounter yellow end pages whose bottom edges evince water damage similar to the front cover. On its 1st page verso a German inscription, written in large characters in pencil, sets it apart from our other copies: “Christologisch! Angriffe aufs Judentum! Verfasser der Missionar M’Caul” (“Christian doctrine! Attack against Judaism! Writings of Missionary McCaul”).

Nothing definitively indicates who wrote this admonishment.

Except for the printer’s statement, in English, the title page — indeed the entire book — is printed primarily in Hebrew. This includes pagination, except for the gathering indicators. Printed in gatherings of four, each four leaf is lettered in Latinate characters. The Hebrew type is Rashi script, with the exception of the Ashkenazi block print headings. These usages perhaps indicate the author or printer knew something of their target audience: most London Jews – particularly those affluent enough to purchase books – were of Sephardic descent.

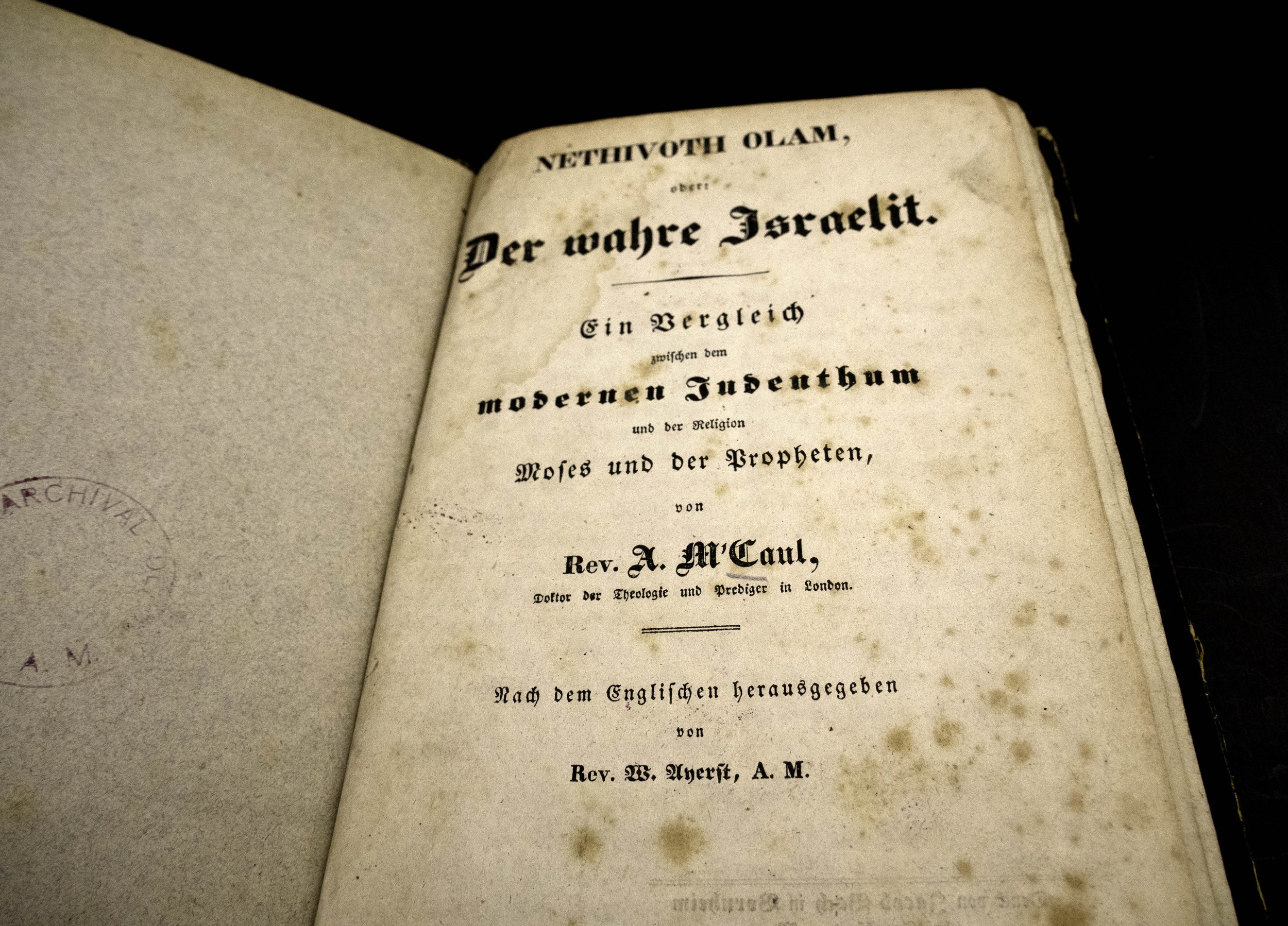

The JPL also holds a copy of a German version of Old Paths, printed in Frankfurt am Main in 1839.

The reader immediately notices several differences between this edition and Netivot. The German contains Biblical verses in Hebrew, along with McCaul’s writings in German translation printed in an ornate Teutonic typeface. That, along with the fact it also shows much more wear than its Hebrew counterpart, again indicates its author and printer knew how to appeal to their audience: a mostly non-Hebrew version would likely interest both Jews with limited Hebrew comprehension as well as non-Jews.

2 round, narrow punctures – one deeper than the other – also mar the German version’s back cover. The deeper cut traverses over 100 pages, about 2/3 of the entire book. Its back end page bears several Hebrew inscriptions that appear to be specific page references for various Talmudic tractates, along with a pencilled inscription in an indecipherable script.

However, the Offenbach Archival Depot ink stamp on its front end page remains this copy’s most interesting feature. Its presence denotes property, seized by the Nazis from its one-time Jewish owners, which could not be repatriated or returned to the latter after World War II’s end. It also allows us to speculate our copy of Netivot, with its warning inscription, travelled a similar path to our collection as not every book acquired by the JPL via Offenbach contains the Depot stamp.