Sefer ha-Gilgulim

(Frankfurt am Main : David ben Nathan Gruenhut, 1684)

-

This “Book of Transmigrations”, based on Kabbalistic teachings, discusses the transmigration of souls. Preoccupied with sexual sins, its lengthy list of punishments for transgressors specifies their consequent resurrections as animals, or unappealing humans. For example, one who had sex with a non-Jewish woman would be reincarnated as a Jewish prostitute.

Gilgulim also discusses the significant Kabbalistic practice of exorcisms in Safed where Isaac Luria — contemporary Kabbalah’s ‘father’ — Vital, and Vital’s son Shmu’el were regarded as powerful exorcists. They considered sudden physical or mental illnesses as manifestations of a sinful soul’s need to inhabit an animal’s body, in order to complete its punishment. If unable to exist there, such a soul would then seek a human host – particularly women, seen as more vulnerable than men. Gilgulim describes, step by step, the exorcism of a chaste woman inhabited by the spirit of a sinful Tripolitan. It also transcribes an interrogation of that spirit to understand how he came to inhabit the woman’s body.

Although Vital is our sole source of Luria’s concepts, in Gilgulim Vital credits him for originating many ideas elaborated upon by Vital. For one, Luria interprets transmigration as good for the Jewish people as “good” souls can return and work with their current, reincarnated selves to right prior wrongs. Vital then posits a single soul’s division into nefesh (animus), ruah (spirit), and neshamah (soul) renders it able to experience multiple fates. He alleviates the focus on and anxieties surrounding sin, maintaining that reincarnation can prepare one’s soul for ascent, and sin can be repaired, if that soul’s genealogy can be ascertained and seek out prior sins that require atonement. Vital suggests that if everyone undertakes this process, the entire universe can be made perfect.

-

Hayyim ben Joseph Vital (1542-1620) was born in Safed, a centre of Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism. Despite being a promising, young, married Torah student, his studies and marriage both left him unfulfilled. Soon, Vital abandoned his wife and Elijah supposedly appeared to him in a dream, persuading him his destiny as a Kabbalist. Vital then spent 2 years studying alchemy, and had another vision of Elijah confirming that he would write a commentary on the Zohar.

By this point, Vital was a student and member of Safed rabbi and principal Kabbalist Moses ben Jacob Cordovero’s inner circle. However, once Isaac Luria arrived there in 1570, and Cordovero died shortly afterwards, Vital and his fellow disciples turned to Luria. Long familiar with Luria’s work, Vital became his foremost disciple. When Luria died in 1572, Vital succeeded him as the Safed Kabbalists’ leader. He subsequently began writing down Luria’s teachings; in this way, Vital became a critical touchstone for historians looking for insight into Luria’s life, work, and students.

Vital eventually left Safed, spending time in Egypt, Ein al-Zeitun, and Jerusalem before settling in Damascus. There, he led the Sicilian Jewish community and wrote the Bible commentary Sefer Eẓ ha-Da’at, his first original work, of which only parts are extant. He then returned to Jerusalem, where in 1590 his teacher Rabbi Moses Alshekh nominally ordained Vital as a rabbi. He then travelled to Safed, falling ill and bedridden for over a year. In 1594, Vital permanently returned to Damascus where he lectured daily on the Kabbalah, and produced Kabbalistic texts until his death.

-

David ben Nathan Gruenhut , a German Talmudist and Kabbalist, first printed Gilgulim in 1682. However, the Frankfurt rabbinate blocked its initial distribution, seeing all Kabalistic works as an intrinsic part of the threat to it from Shabbateanism. Still, Gruenhut managed to arrange its 1684 reprinting (one copy held by the JPL) under a Christian printer’s aegis. He then left Frankfurt, serving as a rabbi in several nearby towns, before returning as a scholar at the bet midrash (public Jewish study centre) founded by Prague chief rabbi David Oppenheim. Gruenhut printed other notable books, two for which he added his own commentaries: 15th century German rabbi and Talmudist Jacob Weil’s Tov Ro’i (1702), on the laws of ritual slaughter, and Judah ben Samuel of Regensburg’s Sefer Hasidim (1712), a seminal 13th-century text of the Hasidei Ashkenaz mystical movement.

Remarkably, Gruenhut also maintained cordial relations with German Christian Hebraists Johann Andreas Eisenmenger and Johann Jakob Schudt – at least, before they published their anti-Semitic works. For Eisenmenger’s edition of the Bible, Gruenhut contributed a complimentary preface; while Schudt wrote the preface to Gruenhut’s edition of Kimhi’s commentary on Psalms, and printed a High German translation of the traditional Purim play celebrated by Prague and Frankfurt’s Jews (1716).

-

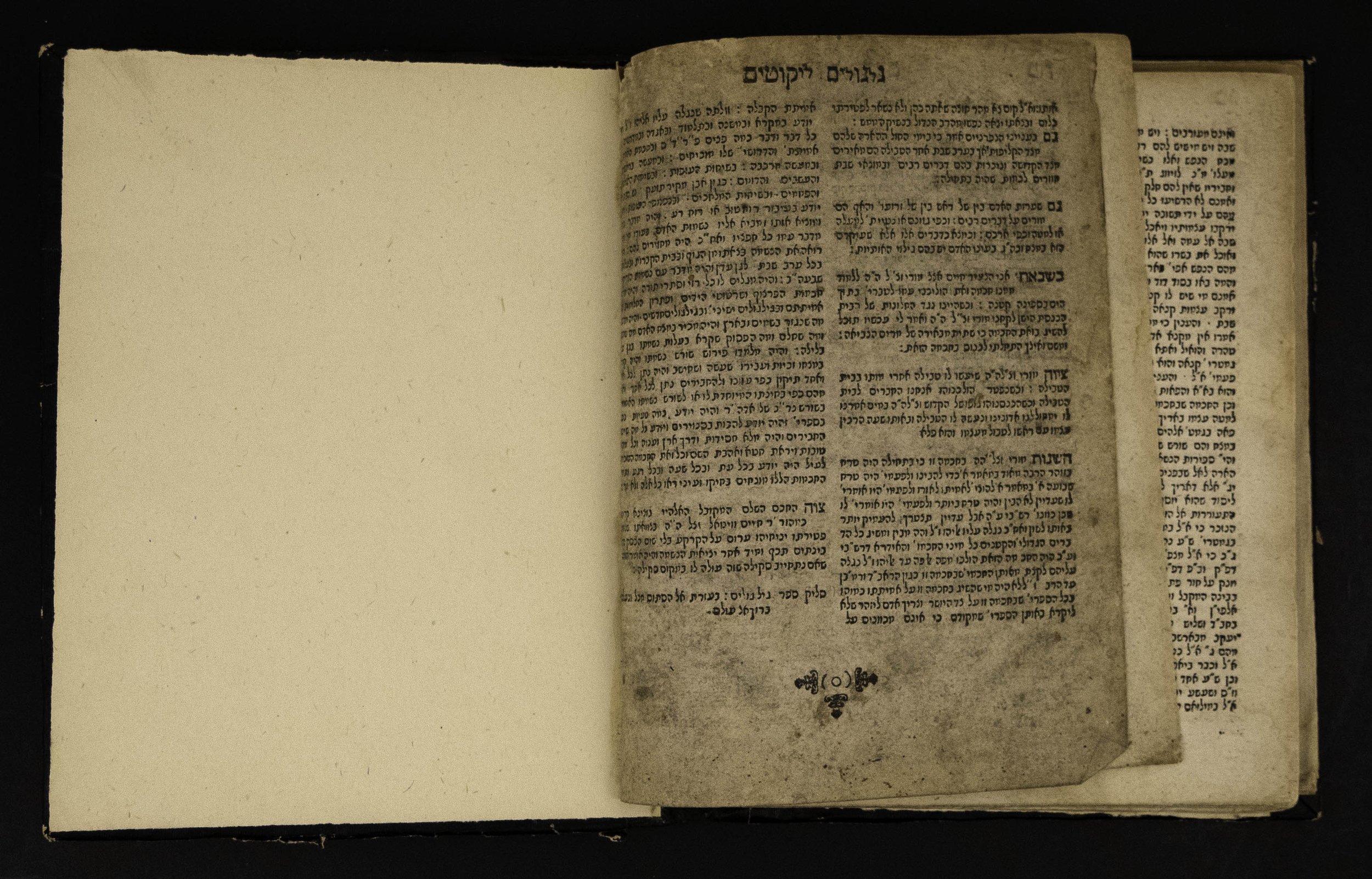

The JPL’s 1684 edition measures 19.5 x 15.5 cm x 1.5 cm. Like many of our collection’s Kabbalistic texts, its 82 leaves render it a relatively slender volume. Evidently rebound, its back and front boards were rewrapped in a black paper almost completely detached from the front cover. The spine, labelled only with a small, glued paper with the book title inked in minuscule characters, indicates the modest means of the rebinding’s underwriter. Both the back and front end-pages have been replaced with a much newer, thicker paper. All that remains of the original book is the text proper; even the title page is missing. A brief, handwritten, largely illegible note in fading brown script on the first page’s top left-hand corner is the sole indicator of any previous ownership.